Design Document: DataNode for Distributed Filesystem

Introduction

Hadoop Distributed File System, Ceph, The Google File System, Facebook's Tectonic, Alibaba's Pangu and Baidu's CFS are all successful distributed file systems (DFS) known for their performance, reliability, and scalability. These systems typically consist of namenodes for metadata management, datanodes for data storage, and client interfaces for user interaction.

This document proposes a new datanode architecture to meet evolving demands. Traditional DFS tenants like data warehouses and blob storage are being joined by AI workloads, which introduce new requirements. Additionally, the growing adoption of NVMe in data centers calls for a fresh approach to datanode design.

Terminologies

- Segment: A segment is a logical unit of storage managed by the NameNode. A file is split into one or more segments, which are then distributed across DataNodes for storage.

- Chunk: The actual data for a segment is stored as chunks on DataNodes. Each segment usually has multiple chunks (commonly three) distributed across different DataNodes to ensure redundancy and reliability. The NameNode keeps track of which DataNodes store the chunks for each segment. When a segment is read or written, the client interacts with one or more chunks on the respective DataNodes.

- Sector: A sector is a small unit within a chunk, and each sector has its own checksum for data integrity.

- Block: Block is a reserved term used for block devices and SPDK.

Design Goals

Scale-Out Architecture

- The DFS Should Be Fully Scale-Out: A truly scalable distributed file system needs its components to scale independently. This includes not only the storage but also the computational responsibilities distributed across the system.

- DataNode Should Take On Certain Calculations: If the NameNode handles all operations, it becomes a bottleneck as the number of DataNodes increases. This would require scaling up the NameNode, making the overall system less scalable.

- Chunk Allocation as an Example: When a client writes data, the system needs to determine the chunk locations, typically as a list like

[(ip=192.168.0.1, disk=nvme0n1, offset=8MiB, len=1MiB), ...]. While the NameNode should calculate the IP and disk information, the offset should be calculated by each DataNode to distribute the load. - Cache Eviction in Systems Like Alluxio: In caching file systems, DataNodes should handle cache eviction decisions. Offloading such tasks to DataNodes reduces the NameNode's workload and allows for more efficient scaling.

- Chunk Allocation as an Example: When a client writes data, the system needs to determine the chunk locations, typically as a list like

- Metadata Locality on DataNodes: When partial calculations are handled by DataNodes, the relevant metadata should also reside on the DataNodes. Keeping this metadata localized prevents unnecessary bandwidth usage between NameNodes and DataNodes and simplifies the programming model.

- Metadata Storage on DataNodes: A system is required to store the metadata locally on the DataNodes. This can be either a custom implementation or an existing solution like a key-value store. I prefer using a mature KV store such as RocksDB for this purpose, given its reliability and performance.

DataNode should take on certain calculations to ensure a truly scale-out architecture. As a result, we need a RocksDB-based metadata storage on each DataNode to support these operations.

Write Fast, Read Fast

- The time taken to process a client's write request should be equivalent to the time of one disk write operation on the DataNode. If a client's write request results in two sequential disk writes, the total time will be longer, which we aim to avoid.

- HDFS as a Counterexample: In HDFS, when a DataNode writes chunk data as an ext4 file, at least two sequential disk writes are required - one for the ext4 metadata journal and another for the actual data.

- Another Counterexample: In a simple implementation, the DataNode first writes chunk metadata (e.g., to RocksDB) and then performs a separate disk I/O operation for the actual data. This results in two sequential disk writes, which we aim to avoid.

- To optimize read performance, each client's read request should result in only one I/O read operation. To achieve this, we must cache chunk metadata (e.g., chunk location) in memory, so that there's no need to retrieve it from disk before serving the read request.

- Bypassing Kernel and CPU Overhead: The design should leverage advanced technologies that bypass kernel and CPU overheads, such as VFIO, SPDK, DMA, RDMA, and GPUDirect. These technologies minimize data copying and reduce latency, allowing for faster and more efficient data writes.

The goal is to ensure that DataNodes perform the fewest possible disk operations - ideally just one. If two disk operations are necessary, they should be performed in parallel to minimize latency. And each operation should be as fast as possible.

Read Efficiency: A New Data Layout for Big Data and AI Scenarios

- In Big Data Scenarios:

- Compute engines often need to read only small portions of large chunks. For example, when reading statistics from a Parquet file, only a subset of the chunk is required, not the entire chunk.

- Instead of using a single checksum for an entire chunk, small units within the chunk should each have their own checksum. For instance, Alibaba's Pangu splits a chunk into multiple sector units, each with its own CRC checksum. This allows the system to read only the necessary sectors and their corresponding checksums, instead of the entire chunk, optimizing performance when serving client read requests.

- In AI scenarios, entire chunk are read using DMA/RDMA/GPUDirect, requiring a contiguous data layout for efficient data movement.

- Big Data workloads benefit from interrupted layouts with checksums for small units, while AI workloads prefer contiguous data for efficient sequential access. To effectively serve both scenarios, a new data layout is required:

- The data is divided into sectors, and each sector has its own CRC for integrity verification. These CRC values are stored alongside the metadata (e.g., in RocksDB), rather than interleaved with the actual data. This ensure that the data remains contiguous on disk.

- To complement the new data layout, we need a new write process that can handle parallel writes for both metadata and data to minimize latency.

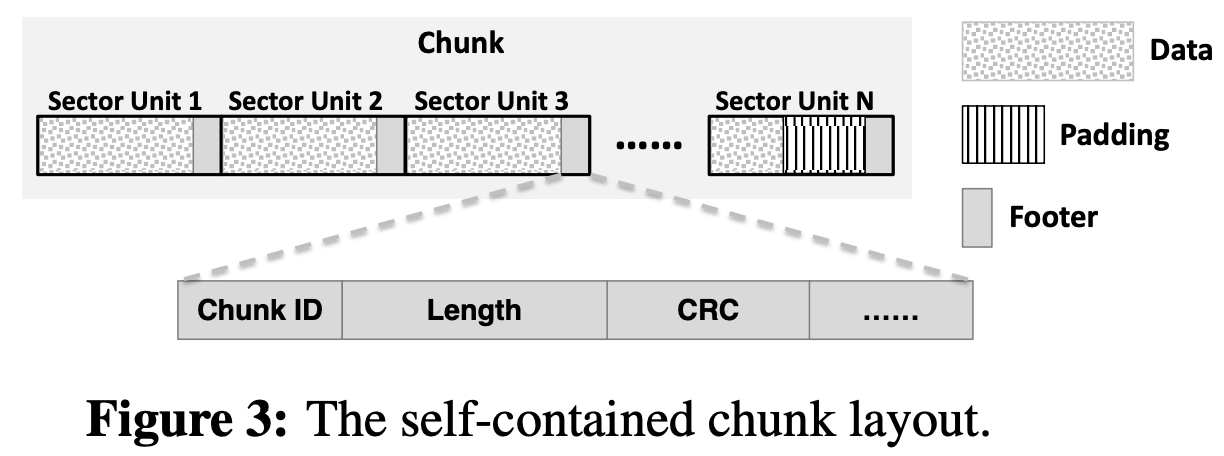

Self-contained Chunk Data Layout for Recovery

The goal is to ensure that even if metadata stored in the NameNode (e.g., directory tree) and metadata stored in the DataNode (e.g., chunk locations) are both lost, the system can still recover most of the data. This is crucial for maximizing data recovery in the event of unexpected disasters such as software bugs or operational errors. A self-contained chunk layout allows the system to reconstruct data independently, without relying on external metadata.

Disk Partition

In this section, we discuss how the disk should be partitioned. The disk is divided into two primary sections:

- Metadata Partition: This partition is dedicated to storing metadata. The metadata partition is further subdivided into two distinct parts:

- DBFS is a simple file system tailored to support RocksDB. It supports basic file operations such as creating append-only files, reading files, and deleting files.

- RocksDB on DBFS: The second subdivision is reserved for RocksDB, which is built on top of DBFS.

- Data Partition: This partition holds the actual chunk data.

Super Meta, Edit Log, and Snapshot Format

All critical metadata in the system - such as the super meta, edit log, and snapshot - follows the same structured format. This format is designed to be self-explanatory and self-contained, ensuring that the system can interpret these regions without relying on additional code logic. The format is as follows:

- Each region starts with a magic number - a unique identifier that signals the type of the region (e.g., super meta, edit log, or snapshot).

- After the magic number, a

uint32_tspecifies the length of the following protobuf message. This ensures that the system knows exactly how many bytes to read for the protobuf. - The protobuf message itself contains a variety of metadata, including a

lengthfield that describes the total size of the region. This length field is crucial because it makes the region self-explanatory - the system can determine the full length of the region from the protobuf alone, without needing to reference external code or metadata. - Finally, the region is padded with zero bytes to reach the required alignment.

Chunk Data Layout

In this section, we will examine the current data layouts used by various DFS implementations and then propose a new layout that optimizes for our design goals, particularly the goals of write fast, read fast, and read efficiency. The data layout is at the heart of the entire DataNode architecture and has a profound effect on how we achieve the above design goals.

This section is divided into two main parts:

- Investigating Current Data Layouts: We will explore the existing data layouts used by popular DFS implementations, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses.

- Proposing a New Data Layout: We will introduce a new layout that addresses the shortcomings of current designs and aligns with our goals. This will be divided into:

- Layout Specification: A detailed explanation of the new data layout, describing how data and metadata are organized on disk.

- Layout Explanation Through Read/Write Process: A brief walk-through of how the proposed layout optimizes the read and write processes, illustrating why this design is more efficient and scalable.

Investigating Current Data Layouts

We will now investigate the data layouts of various distributed file systems and clarify the sources of this information.

| HDFS | Ceph | GFS | Pangu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metadata and Data Layout | Split | Split | Split | Colocate |

| Disk Write Operations per Client Write Request | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Disk Read Operations per Client Read Request | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Read Efficiency for Small Portions of a Chunk | High | High | High | High |

Extra memcpy Required for Full Chunk Read |

No | No | No | Yes |

The table highlights the tradeoff: if data and metadata are colocated, an extra memcpy is needed when reading the entire chunk due to interspersed checksums between data sectors. Conversely, if they are split, a client write request requires two disk write operations.

The following sources were used to gather the information presented in the table above:

Ceph Source: File Systems Unfit as Distributed Storage Backends: Lessons from 10 Years of Ceph Evolution

Ceph performs two disk write operations, one for data and one for metadata:

For incoming writes larger than a minimum allocation size (64 KiB for HDDs, 16 KiB for SSDs), the data is written to a newly allocated extent. Once the data is persisted, the corresponding metadata is inserted to RocksDB.

Ceph also offers other valuable insights:

BlueStore computes a checksum for every write and verifies the checksum on every read.

While multiple checksum algorithms are supported, crc32c is used by default because it is well-optimized on both x86 and ARM architectures, and it is sufficient for detecting random bit errors.

With full control of the I/O stack, BlueStore can choose the checksum block size based on the I/O hints. For example, if the hints indicate that writes are from the S3-compatible RGW service, then the objects are read-only and the checksum can be computed over 128 KiB blocks.

BlueStore achieves its first goal, fast metadata operations, by storing metadata in RocksDB. BlueStore achieves its second goal of no consistency overhead with two changes. First, it writes data directly to raw disk, resulting in one cache flush for data write. Second, it changes RocksDB to reuse WAL files as a circular buffer, resulting in one cache flush for metadata write - a feature that was upstreamed to the mainline RocksDB.

GFS Source: The Google File System

A chunkis broken up into 64 KB blocks. Each has a corresponding 32 bit checksum. Like other metadata, checksums are kept in memory and stored persistently with logging, separate from user data.

Pangu Source: More Than Capacity: Performance-oriented Evolution of Pangu in Alibaba

A chunk includes multiple sector units, where each sector unit includes 3 elements: data, padding, and footer. The footer stores chunk metadata, such as chunk ID, chunk length, and the CRC checksum.

Proposing a New Data Layout

The following key design elements are highlighted:

- Splitting Metadata and Data: The chunk metadata (such as checksums and other metadata) and the actual data are stored separately.

- Metadata Copy for Recovery: For recovery purposes, a copy of the metadata is appended at the end of the chunk data.

- Self-Contained Data Format:

- The data ends with a magic number.

- After the magic number, there's a protobuf length.

- Next comes the protobuf message itself, which contains the serialized metadata or data structure.

- Finally, the data is zero-padded to align with the underlying storage requirements.