Paper Interpretation - Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication

Introduction

The paper Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication introduces an innovative approach to jointly optimizing concurrency control and consensus protocols, offering valuable insights that enhance my understanding of related works such as There Is More Consensus in Egalitarian Parliaments and CEP-15: Fast General Purpose Transaction. The Q&A section on the accompanying blog captures the questions I had when initially exploring this paper.

Our key insight is that existing transactional storage systems waste work and performance by integrating a distributed transaction protocol and a replication protocol that both enforce strong consistency.

Maintaining the ordered log abstraction means that replicated transactional storage systems use expensive distributed coordination to enforce strict serial ordering in two places: the transaction protocol enforces a serial ordering of transactions across data partitions or shards, and the replication protocol enforces a serial ordering of operations within a shard.

By enforcing strong consistency only in the transaction protocol, TAPIR is able to commit transactions in a single round-trip and schedule distributed transactions with no centralized coordination.

To support IR’s weak consistency model, TAPIR integrates several novel techniques:

- Loosely synchronized clocks for optimistic transaction ordering at clients.

- New use of optimistic concurrency control to detect conflicts with only a partial transaction history.

- Multi-versioning for executing transactions out-of-order.

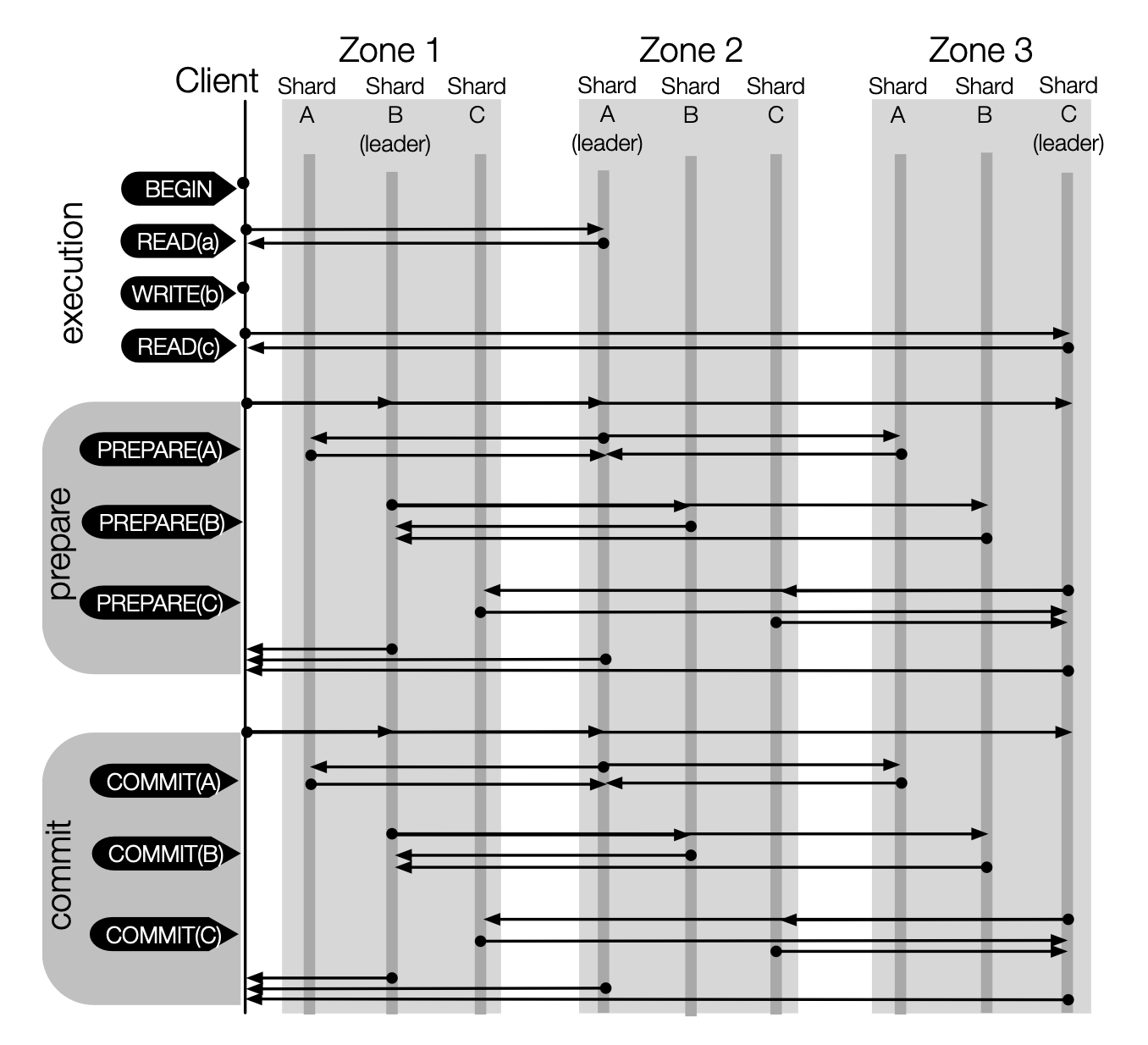

As illustrated in Figure 2, the two-phase commit protocol, when applied with viewstamped replication or Raft, requires a minimum of two round-trip times (RTTs). Considering the prepare phase within a Raft-based replication scenario: initially, the client communicates its intention to prepare a transaction to the leaders of Shard A, Shard B, and Shard C. Subsequently, each leader synchronizes this preparation event with its followers. Upon receiving affirmative responses from a majority, a leader then conveys its acknowledgment back to the client. In conclusion, the transaction preparation process from the client's perspective incurs a total of two RTTs: the first RTT occurs between the client and the leaders across Shard A, Shard B, and Shard C, while the second RTT takes place between these leaders and their respective followers.

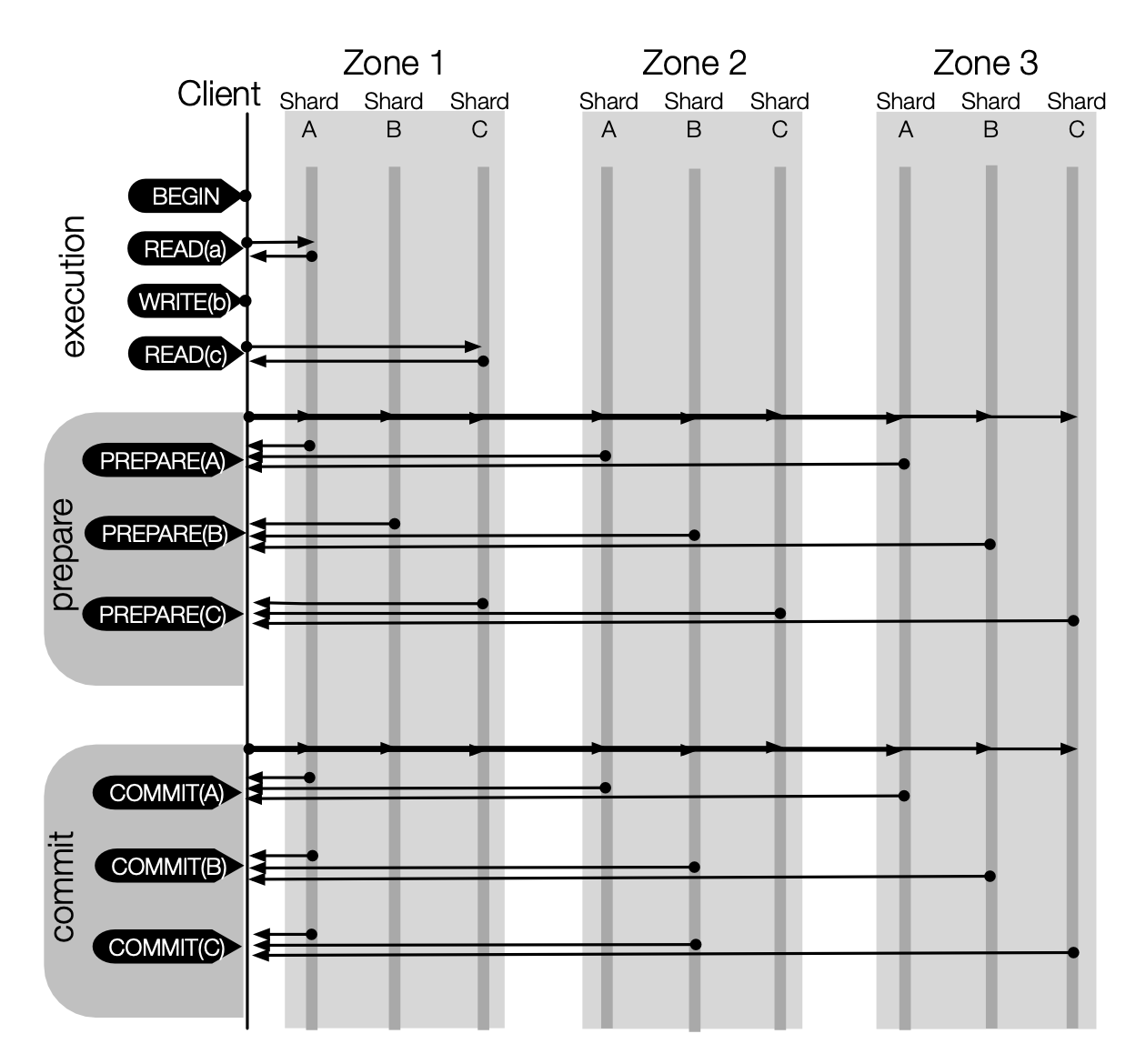

Figure 4 shows the messages sent during a sample transaction in TAPIR. Compared to the protocol shown in Figure 2, TAPIR has three immediately apparent advantages:

- Reads go to the closest replica. Unlike protocols that must send reads to the leader, TAPIR sends reads to the replica closest to the client.

- Successful transactions commit in one round-trip. Unlike protocols that use consistent replication, TAPIR commits most transactions in a single round- trip by eliminating cross-replica coordination.

- No leader needed. Unlike protocols that order operations at a leader, TAPIR replicas all process the same number of messages, eliminating a bottleneck.

Q&A

Q&A on TAPIR Fundamentals

Understanding the Key Distinctions Between \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) and \(\operatorname{Commit}(transaction, timestamp)\) Operations

The most significant distinction is that replicas can independently decide to return \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) or \(\text{ABORT}\), without needing to communicate with other replicas. This independent decision is based on the outcome of the TAPIR validation checks, which may vary due to the different states that each replica might be in at the time of validation. Consequently, replicas may yield varying responses. The final decision is reached by a majority vote amongst the replicas, a process that is essentially a form of consensus. This is why the original paper refers to the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) as a consensus operation. In contrast, the \(\operatorname{Commit}(transaction, timestamp)\) operation is processed identically by all replicas, who then return the same result: they simply commit the transaction. Therefore, the \(\operatorname{Commit}(transaction, timestamp)\) operation is termed an inconsistent operation.

The result of \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) at each replica depends on the outcome of the TAPIR validation checks. As noted, TAPIR validation checks have four possible outcomes.

Thus, in addition to normal-case execution, TAPIR performs the following checks for each operation:

- \(\operatorname{Prepare}\): If the transaction has been committed or aborted (logged in the transaction log), ignore. Otherwise, TAPIR validation checks are run.

- \(\operatorname{Commit}\): Commit the transaction to the transaction log and update the data store. If prepared, remove from prepared transaction list.

- \(\operatorname{Abort}\): Log abort in the transaction log. If prepared, remove from prepared list.

TAPIR prepares are consensus operations, while commits and aborts are inconsistent operations.

Let's delve deeper into why the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) operation is designed as a consensus operation, while the \(\operatorname{Commit}(transaction, timestamp)\) operation is an inconsistent operation. TAPIR employs a typical two-phase commit (2PC) protocol, which requires a transaction to be committed only if all participating shards confirm that there are no conflicts. Once this confirmation is given, the decision to commit or abort is final, and thus, it should be uniformly persisted across all replicas of each shard. In other words, the replicas do not need to reconsider the decision; they only need to execute it, making it an inconsistent operation. Conversely, during the preparation phase, TAPIR necessitates that each replica independently performs validation checks. The final decision is derived from aggregating these individual responses. For this reason, it must be a consensus operation.

Evaluating the Necessity of Finalizing Successful but Unfinalized \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) Operations

If the \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) times out without finalizing the result in one of the participant shards, then the TAPIR client must take a slow path to finish the transaction. If \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) succeeded with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) in every shard, the client commits the transaction, otherwise it aborts. To complete the transaction, the client first logs the outcome of the transaction to the backup coordinator group. It then notifies the client, and sends a \(\operatorname{Commit}\) or \(\operatorname{Abort}\) to all participant replicas.

Is there a need to impose an obligation to finalize \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) operations that have been successful but remain unfinalized, specifically in cases where the transaction has not been committed via the fast path and subsequently enters the slow path?

Without that obligation in place, after a system endures up to \(f\) simultaneous failures and subsequently undergoes recovery, the most critical scenario that could emerge are as follows. Because these operations had been successful but were not finalized at the time of system failures, following the recovery process, it is possible that replicas might achieve different consensuses. After the system has recovered from the failures, it's possible to find that some \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) operations have resulted in \(\text{ABORT}\), yet the corresponding transaction has already been committed through the slow path.

At first glance, these scenarios might suggest the presence of inconsistency within the system in the absence of such an obligation. However, this is not an issue of concern if the replicas are designed to unconditionally accept and process the \(\operatorname{Commit}(transaction, timestamp)\) operation, regardless of the state of the corresponding \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) operation. By adhering to this straightforward rule, any appearance of inconsistency is effectively resolved, ensuring the system maintains consistent post-recovery.

In conclusion, such an obligation is unnecessary.

Evaluating the Necessity of the Slow Path for Abortion Processes

If the \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) times out without finalizing the result in one of the participant shards, then the TAPIR client must take a slow path to finish the transaction. If \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) succeeded with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) in every shard, the client commits the transaction, otherwise it aborts. To complete the transaction, the client first logs the outcome of the transaction to the backup coordinator group. It then notifies the client, and sends a \(\operatorname{Commit}\) or \(\operatorname{Abort}\) to all participant replicas. The client uses the same slow path to abort the transaction if \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) does not succeed in any shard because there were not enough matching responses.

Why should the abortion process also be required to go through the slow path?

Because the TAPIR protocol is not designed to finalize unsuccessful \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) operations. In the event of failures and subsequent recovery, replicas can arrive at divergent consensus outcomes — \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) as opposed to the original \(\text{ABORT}\) consensus. Without the slow path mechanism, a client might erroneously commit a transaction post-recovery that was initially aborted prior to recovery, leading to inconsistency within the system.

We could potentially design an alternative IR protocol capable of finalizing unsuccessful \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) operations, which would allow TAPIR to abort transactions without resorting to the slow path. However, this would add complexity to the overall protocol.

Q&A on Coordinator Recovery

Mechanisms of \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}(transaction, view\text{-}num)\) in Fencing the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(transaction, timestamp)\) Operation

Coordinator recovery uses a coordinator change protocol, conceptually similar to Viewstamped Replication's view change protocol. The currently active backup coordinator is identified by indexing into the list with a coordinator-view number; it is the only coordinator permitted to log an outcome for the transaction.

If the new coordinator does not find a logged outcome, it sends a \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}(transaction, view\text{-}num)\) message to all replicas in participating shards. Upon receiving this message, replicas agree not to process messages from the previous coordinator; they also reply to the new coordinator with any previous \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) result for the transaction. Once the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) is successful (at \(f+1\) replicas in each participating shard), the new coordinator determines the outcome of the transaction in the following way.

In the Single-Decree Synod protocol from The Part-Time Parliament, a fencing mechanism is employed to halt the advancement of consensus on lower ballots that have not yet achieved consensus:

Upon receipt of a \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) message from \(p\) with \(b > \operatorname{nextBal}(q)\), priest \(q\) sets \(\operatorname{nextBal}(q)\) to \(b\) and sends a \(\operatorname{LastVote}(b, v)\) message to \(p\), where \(v\) equals \(\operatorname{prevVote}(q)\). A \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) message is ignored if \(b \le \operatorname{nextBal}(q)\).

This critical fencing mechanism is also implemented within coordinator recovery as the coordinator change protocol. In this context, \(view\text{-}num\) is analogous to the Single-Decree Synod protocol's ballot number \(b\), and \(transaction\) is comparable to the instance ID. Similar to the Synod's protocol commitment that a \(\operatorname{BeginBallot}(b, d)\) message is ignored if a higher \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b^\prime)\) message has been received, the coordinator change protocol ensures that messages from the previous coordinator are not processed.

Why Must Every Conflicting Transaction Use the Slow Path?

However, every conflicting transaction must have used the slow path.

A transaction is considered conflicting if any of its \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) operations within a shard results in an \(\text{ABORT}\) status, indicating a conflict. As previously discussed, the abortion process is required to go through the slow path. Therefore, by design, every conflicting transaction inevitably takes the slow path.

However, not all transactions that go through the slow path are necessarily conflicting. A transaction that has taken the slow path may also be a non-conflicting transaction that contains any successful but not yet finalized \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) operations. In other words, transactions that use the slow path consist of two types: non-conflicting transactions still awaiting the finalization of at least one successful \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) operation, and conflicting transactions.

Why Must the New Coordinator Await the Completion of All Transactions?

In doing so, it receives any slow-path outcome that was logged by a previous coordinator. If such an outcome has been logged, the new coordinator must follow that decision; it notifies the client and all replicas in every shard.

... the new coordinator determines the outcome of the transaction in the following way:

- If any replica in any shard has recorded a \(\operatorname{Commit}\) or \(\operatorname{Abort}\), it must be preserved.

- If any shard has less than \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses, the transaction could not have committed on the fast path, so the new coordinator aborts it.

- If at least \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas in every shard have \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses, the outcome of the transaction is uncertain: it may or may not have committed on the fast path. However, every conflicting transaction must have used the slow path. The new coordinator polls the coordinator (or backup coordinators) of each of these transactions until they have completed. If those transactions committed, it aborts the transaction; otherwise, it sends \(\text{Prepare}\) operations to the remaining replicas until it receives a total of \(f+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses and then commits.

I would like to emphasize the following part:

... the outcome of the transaction is uncertain: it may or may not have committed on the fast path. ... The new coordinator polls the coordinator (or backup coordinators) of each of these transactions until they have completed.

Consider the following, Case 1:

- In the combined context of Part A and Part B, we consider a collective group of \(\lfloor\frac{3f}{2}\rfloor\) replicas. Each replica in this group first receives an \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\gamma, t_\gamma)\) operation, and subsequently receives an \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation. Given that transactions \(\gamma\) and \(\tau\) are in conflict, and the replicas have already responded to \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\gamma, t_\gamma)\) with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\), they are compelled to respond to \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) with \(\text{ABORT}\).

- In Part A, there are \(f\) replicas. These replicas do not respond to the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) message from the new coordinator.

- In Part B, there are \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\) replicas. These replicas inform the new coordinator of their previous \(\text{ABORT}\) response for the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation associated with transaction \(\tau\).

- In Part C, a group of \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas is considered. These replicas have not received any operations about transaction \(\gamma\). Consequently, they respond to the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\). Upon receiving a \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) message, they inform the new coordinator of their previous \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) response for the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation associated with transaction \(\tau\).

- After successfully receiving \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) responses from a combined total of \(f+1\) replicas, encompassing both Part B and Part C (thereby the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) is successful), the new coordinator is unable to commit the transaction \(\tau\). Such a commitment could result in a conflict where both transactions \(\gamma\) and \(\tau\) are committed within the system, leading to inconsistency. This situation arises from the potential that the client of transaction \(\gamma\) might obtain \(f+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses and attempt to commit the successful but not yet finalized transaction \(\gamma\) via the slow path at some future point (this action is unstoppable).

- At time \(t_1\), the client of transaction \(\gamma\) receives \(\lfloor\frac{3f}{2}\rfloor\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses from replicas in Part A and Part B.

- At time \(t_5\), the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) for transaction \(\tau\) is successful, with \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas of Part C providing \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses for transaction \(\tau\), and \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\) replicas of Part B providing \(\text{ABORT}\) responses for transaction \(\tau\). The new coordinator must refrain from committing transaction \(\tau\) at this point to avoid system inconsistency at \(t_9\).

- At time \(t_8\), the client of transaction \(\gamma\) initiates the slow path, writing the commit outcome of transaction \(\gamma\) to a backup coordinator group.

- At time \(t_9\), the client of transaction \(\gamma\) completes the slow path, with the commit outcome of transaction \(\gamma\) now recorded by the backup coordinator group.

Consider the following, Case 2:

- In Part D, a group of \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\) replicas is considered. Each replica in this group first receives an \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\gamma, t_\gamma)\) operation, and subsequently receives an \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation. Given that transactions \(\gamma\) and \(\tau\) are in conflict, and the replicas have already responded to \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\gamma, t_\gamma)\) with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\), they are compelled to respond to \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) with \(\text{ABORT}\).

- In the combined context of Part E and Part F, we consider a collective group of \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas. Each replica in this group have not received any operations about transaction \(\gamma\). Consequently, they respond to the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\).

- In Part E, there are \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas. These replicas inform the new coordinator of their previous \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) response for the \(\operatorname{Prepare}(\tau, t_\tau)\) operation associated with transaction \(\tau\).

- In Part F, there are \(f\) replicas. These replicas do not respond to the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) message from the new coordinator.

- After successfully receiving \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) responses from a combined total of \(f+1\) replicas, encompassing both Part D and Part E (thereby the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) is successful), the new coordinator is unable to abort the transaction \(\tau\). Aborting the transaction \(\tau\) at this stage could lead to inconsistencies, as there is a possibility that the client of transaction \(\tau\) has already committed \(\tau\) on some replicas prior to this coordinator recovery.

- At time \(t_1^\prime\), the client of transaction \(\tau\) receives \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses from replicas in Part E and Part F.

- At time \(t_2^\prime\), some replicas within Part F receive the \(\operatorname{Commit}(t_\tau, \tau)\) message from the client of transaction \(\tau\).

- At time \(t_3^\prime\), the client of transaction \(\tau\) fails.

- At time \(t_4^\prime\), the new coordinator initiates coordinator recovery.

- At time \(t_5^\prime\), the \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) for transaction \(\tau\) is successful, with \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas of Part C providing \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses for transaction \(\tau\), and \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\) replicas of Part B providing \(\text{ABORT}\) responses for transaction \(\tau\). The new coordinator must refrain from aborting transaction \(\tau\) at this point to avoid system inconsistency.

At times \(t_5\) and \(t_5^\prime\), the new coordinator observes the same set of responses, confirming a successful \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\) with a total of \(f+1\) replicas responding: \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\) replicas send \(\text{ABORT}\) responses, and \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas send \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses. In Case 1, the coordinator cannot commit transaction \(\tau\); in Case 2, it cannot abort transaction \(\tau\). It is stuck in a dilemma.

The only way to resolve this dilemma is to wait for all conflicting transactions to be conclusively committed or aborted. In the above two cases described, if the new coordinator of transaction \(\tau\) has already received \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses for a \(\operatorname{CoordinatorChange}\), then a conflicting transaction \(\gamma\) cannot be finalized through the fast path. This is because the client of transaction \(\gamma\) will not be able to receive \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses for the corresponding \(\operatorname{Prepare}\) operation. As a result, transaction \(\gamma\) is required to proceed through the slow path. More generally, any conflicting transactions are compelled to take the slow path. This is the rationale behind the author's statement:

However, every conflicting transaction must have used the slow path. The new coordinator polls the coordinator (or backup coordinators) of each of these transactions until they have completed.

A Sketch of the Proof for TAPIR's Correctness

Databases are traditionally expected to maintain four key properties, collectively known as ACID. Atomicity, isolation, and durability are intrinsic guarantees provided by the database system, while consistency is typically ensured by the application logic implemented by the user:

- Atomicity: If a transaction commits at any participating shard, it commits at them all. This is usually secured by the two-phase commit (2PC) mechanism; in cases of client or coordinator failures, the coordinator recovery protocol ensures that a backup coordinator will reach the same decision. Essentially, the integrity of atomicity is maintained by 2PC along with a strict adherence to making no more than one decision per transaction.

- Isolation: There exists a global linearizable ordering of committed transactions. I speculate that the CLOCC protocol ensures that if any two committed transactions in a history do not conflict and adhere to timestamp ordering, then the history is serializable. TAPIR supports this assumption by guaranteeing that any transactions that could potentially conflict intersect at a sufficient number of replicas, a condition that remains valid even after replica or coordinator failovers. Subsequently, any two conflicting transactions are detected by a sufficient number of replicas, which leads to the abortion of at least one of the transactions. Consequently, when any two transactions do not conflict and adhere to timestamp ordering, the result is that the entire history is serializable.

- Duration: Committed transactions stay committed, maintaining the original linearizable order. Duration is principally preserved through the IR protocol, which we will delve into in subsequent discussions.

The following excerpt from Paper Interpretation - Weak Consistency: A Generalized Theory and Optimistic Implementations for Distributed explains the core principles of the CLOCC protocol in ensuring isolation:

The start-depends conflict from Snapshot Isolation can help in understanding Read Object Set (ROS) and Modified Object Set (MOS) tests more effectively. This is particularly useful when utilizing the Start-ordered Serialization Graph. If the timestamp of transaction \(T_i\) is less than the timestamp of transaction \(T_j\) (\(\operatorname{ts}(T_i) < \operatorname{ts}(T_j)\)), then we draw a Start-Depends edge from \(T_i\) to \(T_j\), denoted as \(T_i \stackrel{s}{\longrightarrow} T_j\).

Suppose transaction \(T\) reaches the server for validation such that \(\operatorname{ts}(S_i) < \operatorname{ts}(T) < \operatorname{ts}(S_j)\). Notice that every transaction in the transaction history must be validated against \(T\), not only adjacent transactions.

- To simplify our algorithm, we arrange the read set to always contain the write set (no blind writes), i.e., if a transaction modifies an object but does not read it, the client enters the object in the read set anyway. As a result, we don't need to consider Direct Write-Depends, since accounting for Direct Read-Depends achieves the same effect when determining whether any cycles exist in the SSG. Thus, we need not consider the following four conflicts:

- \(S_i \stackrel{ww}{\longrightarrow} T\)

- \(T \stackrel{ww}{\longrightarrow} S_i\)

- \(T \stackrel{ww}{\longrightarrow} S_j\)

- \(S_j \stackrel{ww}{\longrightarrow} T\)

- The following three conflicts are valid because they have the same directions as the start-dependence conflicts in the SSG.

- \(S_i \stackrel{wr}{\longrightarrow} T\)

- However, if transaction \(S_i\) is prepared but not yet committed, transaction \(T\) should not read versions of objects written by \(S_i\). If \(T\) reads versions of objects written by \(S_i\) before \(S_i\) commits, it would constitute a dirty read if the coordinator ultimately aborts \(S_i\).

- \(S_i \stackrel{rw}{\longrightarrow} T\)

- \(T \stackrel{rw}{\longrightarrow} S_j\)

- Since \(S_i\) is prepared/committed, it could not have observed \(T\)'s updates (there are no dirty reads in CLOCC). In simpler terms, \(T \stackrel{wr}{\longrightarrow} S_i\) is not possible. Similarly, \(T \stackrel{wr}{\longrightarrow} S_j\) is not possible.

- (1) ROS test. This test validates the objects that have been read by \(T\). Let \(S_k\) be the transaction from which \(T\) has read \(x\), i.e., \(\operatorname{ts}(S_k)\) is equal to the value of \(\text{install_ts}\) in \(x\)'s ROS tuple.

- (1a) If \(\operatorname{ts}(S_k) < \operatorname{ts}(S_i)\), then the transaction manager (TM) verifies that \(S_i\) has not modified \(x\). This rule disables \(T \stackrel{rw}{\longrightarrow} S_i\).

- (1b) Furthermore, the TM also verifies that \(\operatorname{ts}(T)\) is greater than \(\operatorname{ts}(S_k)\). This rule disables \(S_j \stackrel{wr}{\longrightarrow} T\).

- (2) MOS test. The TM validates \(\operatorname{MOS}(T)\) by verifying that \(T\) has not modified any object \(y\) that has been read by \(S_j\). This rule disables \(S_j \stackrel{rw}{\longrightarrow} T\).

Q&A on IR Fundamentals

Finalized vs. Successful But Not Finalized Operations: Understanding the Distinction

The fundamental differences between finalized and successful but not finalized operations hinge on their respective behaviors in response to replica failures and recoveries. The first distinction addresses the robustness following failures, while the second focuses on the ability to maintain success after a failure has occurred and a subsequent recovery takes place.

The first distinction is that finalized operations can withstand up to \(f\) failures out of \(2f+1\) total replicas — the maximum failure count that still allows the corresponding partition to process client requests. In such a worst-case scenario, there will be at least \((\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1) - f = \lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) functioning replicas out of the \(f+1\) survivors that have acknowledged the operation with a \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) response. This represents a majority of the remaining active replicas, ensuring the operation's success despite the failures.

Conversely, successful but not finalized operations are less resilient. With \(f\) replica failures, it's possible that only \((f+1) - f = 1\) replica is aware it returned a \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) response. This lone replica does not constitute a majority of the living replicas, which means the operation may no longer be considered successful in the face of these failures.

The second distinction is that finalized operations remain successful through replica failures and subsequent recoveries, whereas successful but not finalized operations do not. The specifics of the IR recovery protocol, which guarantees that a failed replica can recover any operation that it may have executed previously and maintain success, will be addressed in the upcoming Q&A section.

The Single-Operation IR Spec

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

Ensuring the Success of Finalized Operations Post-Recovery with the IR Protocol

IR's recovery protocol is carefully designed to ensure that a failed replica recovers any operation that it may have executed previously and can still succeed. Without this property, successful IR operations could be lost. For example, suppose an IR client receives a quorum of responses and reports success to the application. Then, each replica in the quorum fails in sequence and each lose the operation, leading to the previously successful operation being lost by the group.

In A Generalised Solution to Distributed Consensus, Heidi Howard and Richard Mortier propose a generalised solution to consensus that uses only immutable state to enable more intuitive reasoning about correctness, encompassing both Paxos and Fast Paxos as specific instances. In this section, I intend to demonstrate that the IR protocol aligns with this generalized consensus framework, thereby affirming its correctness. I will specifically address the agreement requirement of consensus, which mandates all clients that output a value must output the same value. Given that in IR every operation can only yield a binary outcome - SUCCEED or FAILED, non-triviality is inherently satisfied when clients input these values. However, I will also discuss the protocol's limitations with respect to the progress requirement, acknowledging the potential for IR to be indecisive under certain conditions.

Below is a table designed to align the terminology between the two papers for clarity:

| A Generalised Solution to Distributed Consensus | Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication |

|---|---|

| server | replica |

| quorum | |

| quorum | super-quorum |

| register | |

| register set | view |

| \(v\) is decided. | \(v\) is finalized. |

An important distinction exists between the concepts of quorums in "A Generalized Solution to Distributed Consensus" (GSDC) and "Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication" (IR) that may lead to confusion. To clarify: what GSDC refers to as a quorum is analogous to a super-quorum in IR. In IR, a value \(v\) is considered finalized when it is written to all registers within the same view of a super-quorum \(S\). Conversely, in the context of IR, a regular quorum \(Q\) is utilized for recovery purposes, and writing value \(v\) to all registers in the same view of \(Q\) does not imply the value is finalized.

The following three rules ensure the fulfillment of the agreement requirement:

- Rule 1: Super-quorum agreement. A client may only output a (non-nil) value \(v\) if it has read \(v\) from a super-quorum of replicas in the same view, where a super-quorum consists of \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas.

- Rule 3: Current decision. A client may only write a (non-nil) value \(v\) to register \(reg\) on replica \(r\) provided that if \(v\) is finalized in view \(vw\) by a super-quorum \(S \in \mathcal{S}_{vw}\) where \(r \in S\) then no value \(v^\prime\) where \(v \neq v^\prime\) can also be finalized in view \(vw\). Given that super-quorums intersect, it is guaranteed within a single view, only one value can be finalized.

- Rule 4: Previous decisions. A client may only write a (non-nil) value \(v\) to register \(reg\) provided no value \(v^\prime\) where \(v \neq v^\prime\) can be finalized by the super-quorums in views \(0\) to \(r − 1\). This rule poses challenges to implement; it will be further explained in the following paragraph.

In addition to the three rules from GSDC, IR includes three specific rules:

- Rule 5: Value preservation. If a replica \(r\) has voted for a value \(v\) in view \(vw\), and there are no failures, then replica \(r\) should only vote for \(v\) in any subsequent view \({vw}'\) where \({vw}' > vw\).

- Rule 6: Recovering only myself. During recovery, a failover replica \(r\) is restricted to writing solely to its own register, avoiding writes to registers of other replicas. This approach significantly deviates from that of Paxos.

- Rule 7: View number preservation. If a failure occurs, the view number \(vw\) is preserved and remains usable after failover, while all other states are lost.

Modifing the IR Recovery Protocol for Easier Correctness Proveness

To enhance the original IR Recovery Protocol in alignment with Rule 4: Previous decisions, the following modifications are proposed:

- ...

It then adds the operation to its record.The operation will be recorded at a later stage, as outlined in step 6. - The replica then sends a \(\langle\text{START-VIEW}, val, {vn}_{new}\rangle\), where \(val\) represents the value determined from steps 3.a or 3.b, \({vn}_{new}\) is the max of the view numbers from other replicas.

- Any replica that receives \(\text{START-VIEW}\) checks whether it has not voted for any value other than \(val\). If this conditions is met, the replica updates its current view number to \(\operatorname{max}(vn, {vn}_{new})\), enters the \(\text{NORMAL}\) state, and replies with a \(\langle\text{START-VIEW-REPLY}, {vn}_{new}\rangle\) message. If not, the replica remains in its current state without sending any reply.

- After the recovering replica receives \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor+1\) \(\text{START-VIEW-REPLY}\) responses, it adds \(val\) to its record, enters the \(\text{NORMAL}\) state and resumes processing client requests. At this point, the replica is considered to be recovered.

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

The correctness of the above-modified IR Recovery Protocol is straightforward to establish. Because at least \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor+1\) replicas confirm that they have not written, and will not write (the view number is maintained and remains valid even post-failover), votes for any value other than \(val\). This assurance means that no values other than \(val\) could have been or will be finalized by a quorum of \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) in any prior view. Thus, it is safe for the recovering replica to write \(val\) in \({vn}_{new}\), which is in full compliance with Rule 4: Previous Decisions.

Proving the Correctness of the Original IR Recovery Protocol: A More Complex Task

I have made minor revisions to the original IR Recovery protocol, omitting extraneous steps that could potentially obfuscate the proof process. These modifications are subtle and retain the essence of the original protocol:

- Once the recovering replica receives \(f+1\) responses, it updates its record using the received records: ... It updates its current view number to \({vn}_{new}\) as the max view number received from other replicas, enters the \(\text{NORMAL}\) state and resumes processing client requests. At this point, the replica is considered to be recovered.

- The replica then sends a \(\langle\text{START-VIEW}, val, {vn}_{new}\rangle\), where \({vn}_{new}\) is the max of the view numbers from other replicas.

- Any replica that receives \(\text{START-VIEW}\) checks ... The replica then always replies with a \(\langle\text{START-VIEW}, val, {vn}_{new}\rangle\) message.

After the recovering replica receives \(f\) \(\text{START-VIEW-REPLY}\) responses, it enters the \(\text{NORMAL}\) state and resumes processing client requests. At this point, the replica is considered to be recovered.

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

The complexity in establishing the correctness of the original IR Recovery Protocol arises from its third step. Here, the recovering replica selects the highest view number, denoted as \({vn}_{max}\), from the \(\text{DO-VIEW-CHANGE}\) messages received from other replicas, and then uses this view number in the steps that follow.

Consider the scenario where the response from replica \(r_1\) is \(\langle\text{DO-VIEW-CHANGE}, {val}_1, {vn}_1\rangle\), from \(r_2\) is \(\langle\text{DO-VIEW-CHANGE}, {val}_2, {vn}_2\rangle\), and so on, up to the response from \(r_{f+1}\), which is \(\langle\text{DO-VIEW-CHANGE}, {val}_{f+1}, {vn}_{f+1}\rangle\), with the condition that \({vn}_1 < {vn}_{max}\), \({vn}_2 < {vn}_{max}\), ..., and \({vn}_{f+1} = {vn}_{max}\).

In such a case, only replica \(r_{f+1}\) is promised to not voting for any value other than \({val}_{f+1}\). The remaining replicas, \(r_1\) through \(r_f\), have made no such promisement regarding their respective values \({val}_1\) through \({val}_f\). This lack of promisement could result in a situation where the recovering replica may vote for \(val\) in \({vn}_{max}\), while other replicas might have already finalized a different value, \({val}^\prime\) (where \({val}^\prime \neq val\)), in a previous view number \({vn}_k\) with \({vn}_k < {vn}_{max}\). Thus, demonstrating that the original IR recovery protocol adheres to previous decisions, becomes a challenging endeavor.

I suggest the term Subsequent Decisions: After a non-nil value \(v\) is finalized by the super-quorums in view \(r\), it is guaranteed that no other non-nil value \(v^\prime\) where \(v \neq v^\prime\) can be finalized in subsequent views \(r+1\), \(r+2\), ... I posit, with some uncertainty, that "subsequent decisions" and "previous decisions" are simply different facets of the same consistency constraint, applied to different views -- in essence, they are two sides of the same coin. Contrary to the complexity involved in proving adherence to "previous decisions," demonstrating that the original IR protocol complies with "subsequent decisions" is notably more straightforward.

The proof unfolds as follows: at the juncture when a value \(v\) is finalized, at least \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas are operational and have recorded the value \(v\) in their registers. Should any of these replicas fail thereafter, upon recovery, they will encounter at least \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor+1\) out of \(f+1\) replicas that had \(v\) written in their registers, compelling them to also write \(v\) to their own register. Thus, post-finalization, regardless of how the involved replicas may experience failures, they are destined to re-adopt the value \(v\) upon recovery. With a maximum of \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor-1\) replicas not participating in the finalization process, these may cast their vote for any value. However, their votes are inconsequential to the outcome as they lack the numbers to influence or alter the already finalized value \(v\).

Q&A on Conflict Detection and Ensuring Isolation Correctness

The original paper maintains that isolation is guaranteed by employing optimistic concurrency control and quorum intersection mechanisms. However, I posit there's a flaw in the quorum intersection during failover events. To elaborate, a transaction \(X\) can be committed only if it obtains at least \(f+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses. Nonetheless, in the worst-case scenario, only \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) of the \(f+1\) replicas may independently decide to record and return \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\), with the remaining replicas succumbing to sequential failovers. Consequently, these replicas are compelled to record and send \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) based on the matching \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses from \(f+1\) responses during the recovery protocol. These failover replicas do not execute the operation independently and, consequently, do not perform conflict detection. In such cases, transaction \(X\) could be committed with just \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1\) replicas genuinely detecting conflicts and voluntarily responding with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\). As a result, the condition for quorum intersection may not be satisfied, as the overlap between quorums could be insufficient. If a conflicting transaction \(Y\) had already committed on \(f+1\) replicas, the calculation \((\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil+1)+(f+1)-(2f+1)=-\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor+1\) yields a negative number, indicating an overlap of less than zero, which means there is no guarantee of a common replica between the quorums.

TAPIR solves this problem using optimistic concurrency control and quorum intersection. OCC validation checks occur between the committing transaction and one previous transaction at a time. Thus, it not necessary or a single server to perform all the checks. Since IR ensures that every \(\text{Commit}\) executes at at least 1 replica in any set of \(f+1\) replicas, and every \(\text{Prepare}\) executes at at least \(\lceil\frac{f}{2}\rceil\) replicas in any set of \(f+1\), at least one replica will detect any possible OCC conflict between transactions, thus ensuring correctness.

Because \(\text{Prepare}\) is a consensus operation, a transaction \(X\) can be committed only if \(f+1\) replicas return \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\). We show that this means the transaction is consistent with the serial timestamp ordering of transactions.

If a replica returns \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\), it has not prepared or committed any conflicting transactions. If a conflicting transaction \(Y\) had committed, then there is one common participant shard where at least \(f+1\) replicas responded \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) to \(Y\). However, those replicas would not return \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) to \(X\). Thus, by quorum intersection, \(X\) cannot obtain \(f+1\) \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) responses.

To address the identified flaw, I propose reducing the tolerance for simultaneous failures from \(f\) to \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\). Consequently, during the recovery protocol, a recovering replica would need to gather \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) responses. The "force recover operation", denoted as \(\operatorname{Recover}(op, res)\), would only be invoked if at least \((\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1)+(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1)-(2f+1) \ge f+1\) responses are matching results \(res\). This ensures that a minimum of \(f+1\) replicas, which have independently detected conflicts, respond with \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) before transaction \(X\) is committed. By implementing this change, the requirement for quorum intersection is satisfied, thus upholding the integrity of the isolation guarantee.

Replacing IR with Fast Paxos: A Protocol Substitution Analysis

The inconsistent replication protocol shares many features with Viewstamped Replication. Like VR, inconsistent replication is designed for in-memory replication without relying on synchronous disk writes. The possibility of data loss on replica failure, which does not happen in protocols like Paxos that assume durable writes, necessitates the use of viewstamps for both replication protocols. Our decision to focus on in-memory replication is motivated by the popularity of recent inmemory systems like RAMCloud and H-Base.

IR does not rely on synchronous disk writes; it ensures guarantees are maintained even if clients or replicas lose state on failure. This property allows IR to provide better performance, especially within a datacenter, compared to Paxos and its variants, which require synchronous disk writes and recovery from disk on failure. IR also provide better fault-tolerance because this property allows it to tolerate disk failures at replicas.

The authors highlight that IR is an in-memory replication protocol that operates independently of synchronous disk writes. However, the need for persistence is critical in certain systems, like the metadata components of distributed file systems, where the marginal slowdown due to sequential writes on industrial-grade SSDs is often negligible and tolerable. Consequently, I believe the practical advantages of in-memory replication may not be as significant as suggested. With this perspective, I am keen to explore the integration of synchronous log-writing capabilities into the IR framework. The original paper states:

Given the ability to synchronously log to durable storage (e.g. hard disk, NVRAM), we can reduce the quorum requirements for TAPIR. As long as we can recover the log after failures, we can reduce the replica group size to \(2f+1\) and reduce all consensus and synchronization quorums to \(f+1\).

Considering the capability to synchronously log to durable storage, the benefits extend beyond just lowering quorum requirements for TAPIR. I am contemplating the use of Fast Paxos to replace IR because Fast Paxos is a well-established protocol with broader adoption in industrial applications.

The Modified Fast Paxos, designed as a replacement for the IR protocol, deviates from the original Fast Paxos in several key aspects:

- Transaction Scope: Unlike the original Fast Paxos, which orders multiple transactions, the Modified Fast Paxos protocol handles a single transaction independently. It does not consider the order or relationship with other transactions.

- Fast Round: The initial round is the only one fast round in the protocol. The protocol initiates with a fast round, where a client may propose a \(\text{Prepare}\) command as a consensus operation without a predetermined result (\(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) or \(\text{ABORT}\)). Replicas decide independently whether to record and return \(\text{PREPARE-OK}\) or \(\text{ABORT}\), eliminating the need for inter-replica communication at this stage. This \(\text{Prepare}\) command and its subsequent result are analogous to the client-proposed value in the original Fast Paxos.

- Slow Round: Rounds following the initial one are classified as slow rounds.

- The slow quorum requirement is set at \(f\), consistent with the original Fast Paxos.

- If all phase 1b messages only contain the same \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a)\) value that matches the fast round's ID, but no other ballot IDs, the slow round must receive more than \(\lceil\frac{3f}{2}\rceil+1\) of these messages to move on to phase 2. This step is crucial for detecting conflicting transactions and maintaining isolation correctness, as mentioned previously. In contrast, the original Fast Paxos protocol only requires more than \(f+1\) phase 1b messages to enter phase 2. As a result, the failure tolerance has been decreased from \(f\) to \(\lfloor\frac{f}{2}\rfloor\) in the modified protocol.

- In alignment with Quorum Requirement of the original protocol, the Modified Fast Paxos ensures that every two fast quorums and each slow quorum have non-empty intersection. Consequently, no more than one value can fulfill the original Fast Paxos's Observation 4. During phase 1 of the slow round, if a value satisfying this requirement exists, it should be proposed in phase 2. If no such value exists, the protocol defaults to proposing an \(\text{ABORT}\) for safety reasons.

Reference

- Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication

- GitHub: UWSysLab/tapir

- The Part-Time Parliament

- A Generalised Solution to Distributed Consensus

- Paper Interpretation - Weak Consistency: A Generalized Theory and Optimistic Implementations for Distributed

- There Is More Consensus in Egalitarian Parliaments

- CEP-15: Fast General Purpose Transaction