Paper Interpretation - A Generalised Solution to Distributed Consensus

Introduction

This paper presents an inspiring piece of work. Creating a distributed consensus algorithm from scratch is no easy task, as Leslie Lamport, the Turing Award winner, once said: "...this consensus algorithm follows almost unavoidably from the properties we want it to satisfy." What this paper does beautifully is to demystify this process, showing even those of us who aren't Turing laureates how to design a consensus algorithm from the ground up.

Building upon the insights from this paper, I plan to revisit the proofs of classical Paxos, Flexible Paxos, and Fast Paxos. My aim is to reinterpret and understand them within the framework presented in this paper.

Problem Definition

The classic formulation of consensus considers how to decide upon a single value in a distributed system. We consider systems comprised of two types of participant: servers, which store the value, and clients, which read/write the value. If you have read The Part-Time Parliament, you'll see that the priest's role is like a mix of the server and client roles as defined in this paper. Interestingly, in most consensus literature, the server role combines the functions of both the client and server as defined here. So, when studying consensus in this context, it's best to forget the usual definitions of server and client roles and instead follow Heidi Howard's definition.

An algorithm solves consensus if it satisfies the following three requirements:

- Non-triviality. All output values must have been the input value of a client.

- Agreement. All clients that output a value must output the same value.

- Progress. All clients must eventually output a value if the system is reliable and synchronous for a sufficient period. This requirement rules out algorithms that could reach deadlock, but it doesn't exclude those that could enter a state of livelock or become stuck when the liveness condition isn't satisfied. As termination cannot be guaranteed in an asynchronous system where failures may occur, algorithms need only guarantee termination assuming liveness.

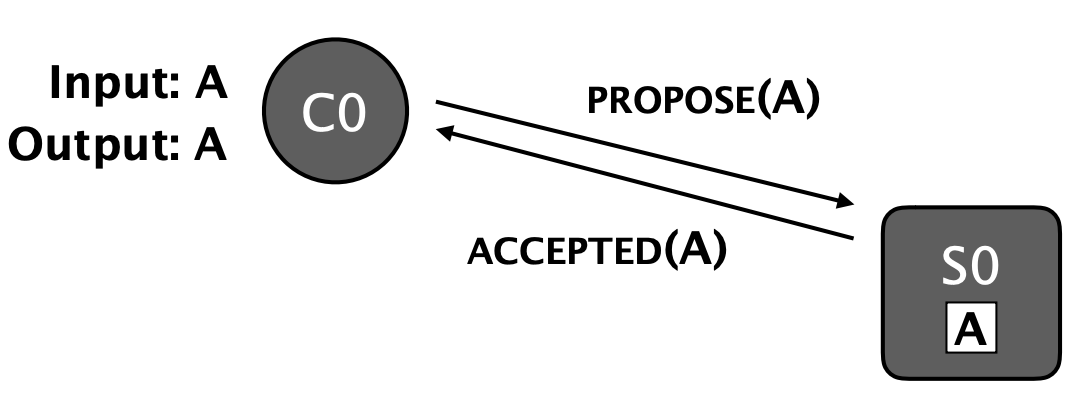

Single-Server Solution

If we have only one server, the solution is straightforward. The server has a single persistent write-once register, \(R0\), to store the decided value. Clients send requests to the server with their input value. If \(R0\) is unwritten, the value received is written to \(R0\) and is returned to the client. If \(R0\) is already written, then the value in \(R0\) is read and returned to the client. The client then outputs the returned value. This algorithm achieves consensus but requires the server to be available for clients to terminate. To overcome this limitation requires deployment of more than one server, so we now consider how to generalise to multiple servers.

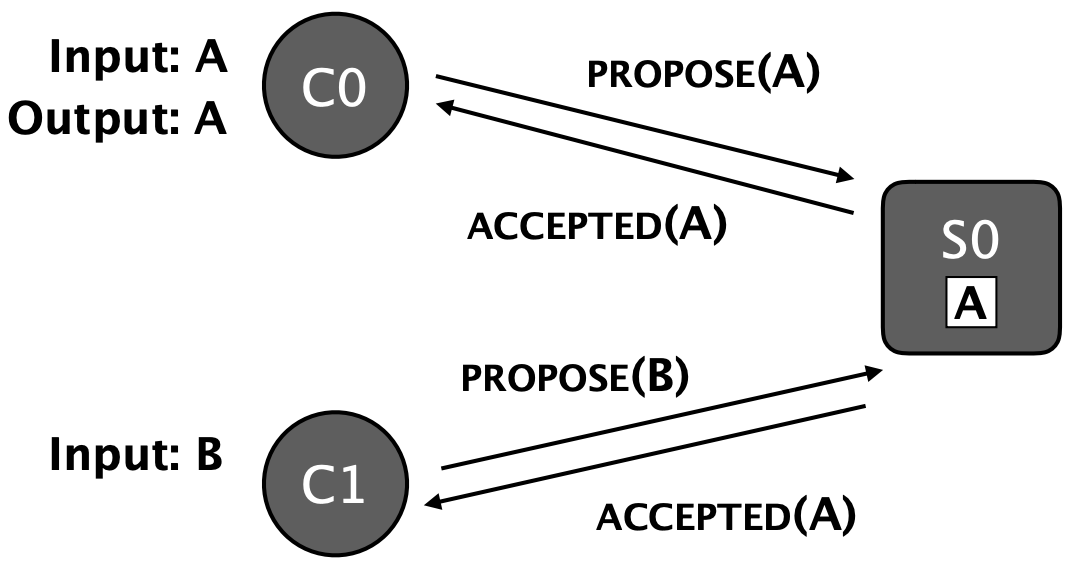

Multiple Servers, Each with a Single Write-Once Persistent Register Solution

We could say a client has to write to all the registers to decide a value, but then that would be even worse than the original algorithm, because now we have three servers and if any one of the three fails, we won't be able to make progress. So let's write to a majority of servers (two or three). That means that there would be an overlap between any two majorities and if one failed, we could still reach a decision. We have got safety, which is great. Unfortunately, we don't actually have the progress property. So we could have a scenario like this, three clients come along, and each of these three clients talks to one of the three servers first and then we've got one register with the value \(A\), one register with the value \(B\), and one register with the value \(C\). We said we wanted immutability property. We're pretty stuck now, there's nothing we can do without overwriting these registers, so we don't have progress.

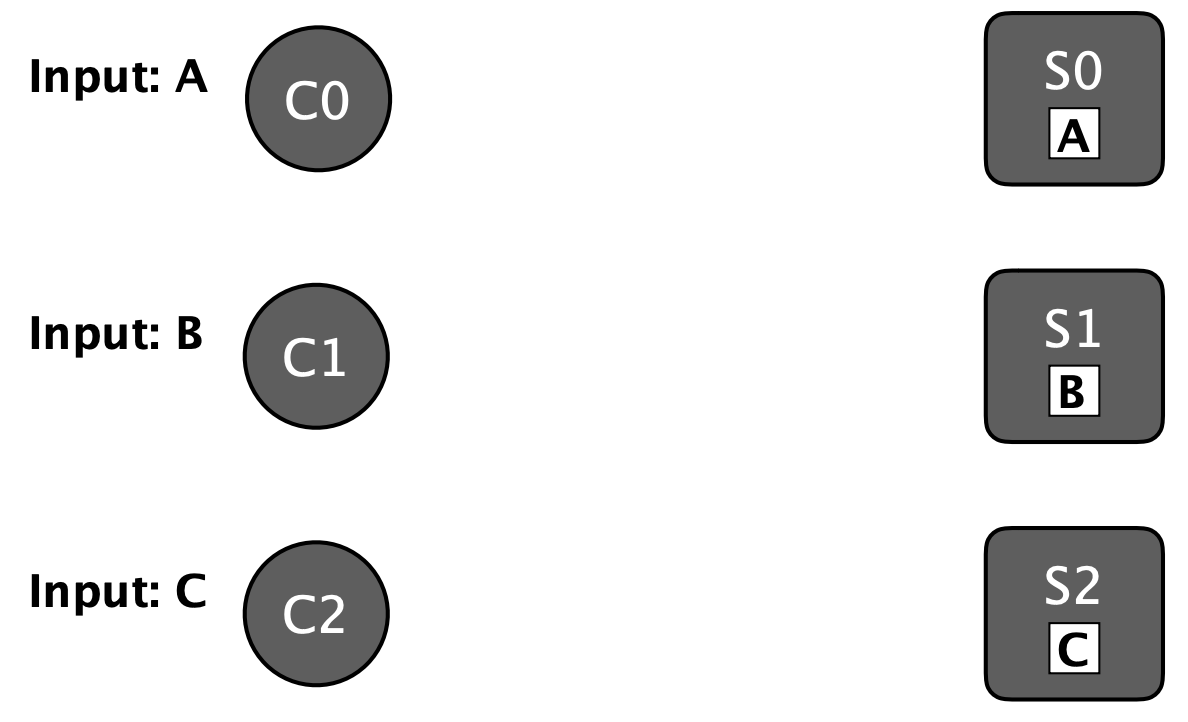

Multiple Servers, Each with Multiple Write-Once Persistent Registers Solution

Consider a set of servers, \(\{S_0, S_1, \ldots, S_n\}\), where each has a infinite series of write-once, persistent registers, \(\{R_0, R_1, \ldots, R_n\}\). Clients read and write registers on servers and, at any time, each register is in one of the three states:

- unwritten, the starting state for all registers; or

- contains a value, e.g., \(A\), \(B\), \(C\); or

- contains nil, a special value denoted as \(\perp\).

The following concepts need to be clarified:

- A quorum, \(Q\), is a (non-empty) subset of servers, such that if all servers have a same (non-nil) value \(v\) in the same register then \(v\) is said to be decided. If you're familiar with distributed systems, you might be thinking about concepts like quorums, majorities, and read-write quorums. However, for now, please set aside any ideas about the necessity for these constructs to intersect. We'll see later whether we do or do not need any intersection properties between them.

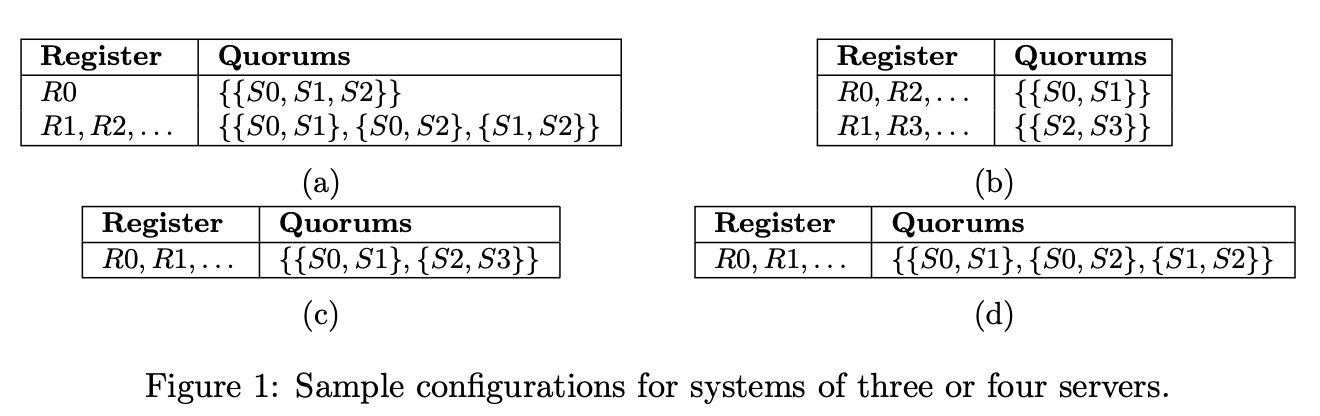

- A register set, \(i\), is the set comprised of the register \(R_i\) from each server. Each register set \(i\) is configured with a set of quorums, \(\mathcal{Q}_i\), and four example configurations are given in Figure 1.

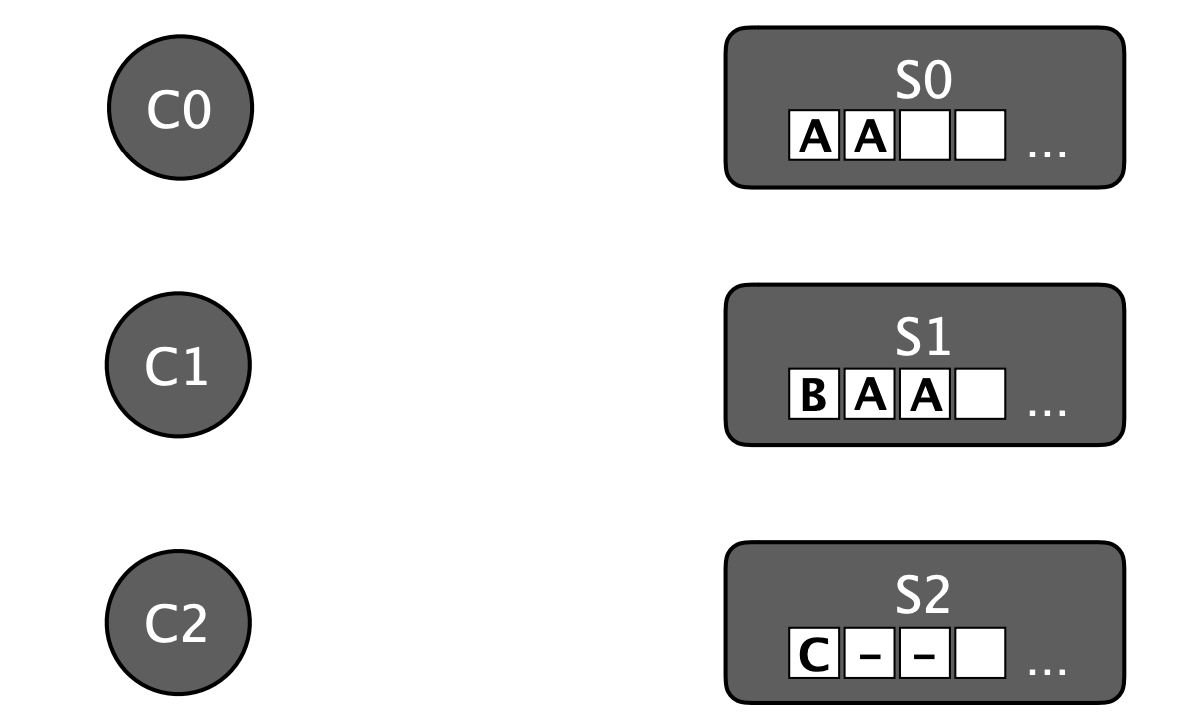

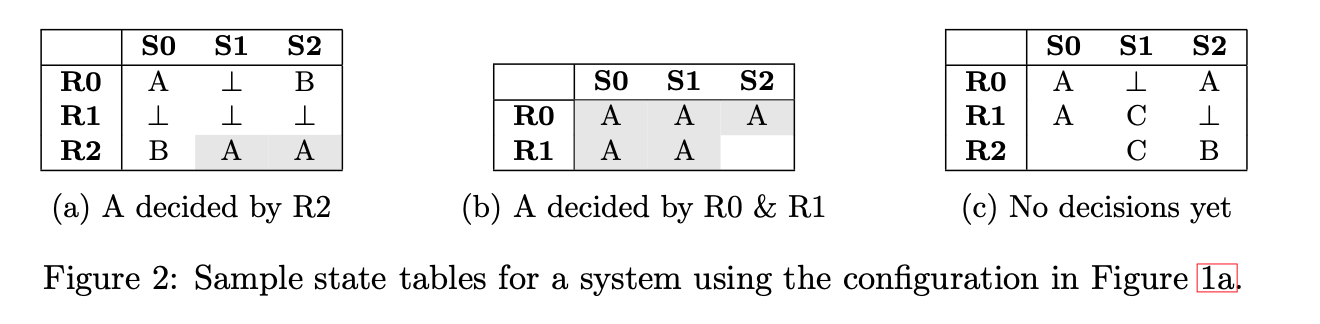

- The state of all registers can be represented in a table, known as a state table, where each column represents the state of one server and each row represents a register set.

We define a value as being decided when we can identify at least one register set \(i\), and a quorum \(Q_i\) such that \(Q_i \in \mathcal{Q}_i\) (where \(\mathcal{Q}_i\) represents the configured quorum sets of the register set \(i\)), and every server in \(Q_i\) has its register \(R_i\) uniformly written with the identical non-nil value \(v\). By combining a configuration with a state table, we can determine whether any decision(s) have been reached (indicated by the gray highlights), as shown in Figure 2.

Correctness

The algorithm adheres to the following four rules, which in turn ensures the satisfaction of the non-triviality, agreement, and progress requirements. Fulfilling these requirements ultimately leads to the successful resolution of consensus.

- Rule 1: Quorum agreement. A client may only output a (non-nil) value \(v\) if it has read \(v\) from a quorum of servers in the same register set. This rule ensures that clients only output values that have been decided. When combined with rules 3 and 4 (which guarantee that at most only one value can be decided), this rule ensures the fulfillment of the agreement requirement.

- Rule 2: New value. A client may only write a (non-nil) value \(v\) provided that either \(v\) is the client's input value or that the client has read \(v\) from a register. This rule ensures the fulfillment of the non-triviality requirement.

- Before a client writes a value to a register \(R_i\) in register set \(i\), it needs to ensure that no other values could be decided in register sets \(0\) through \(i\) (inclusive). The client plans to write into register \(R_i\); however, it's the client's responsibility to verify that none of the previous registers could decide on a different value prior to doing so. This is a crucial step for maintaining safety. All clients must perform this check to prevent conflicting decisions.

- Interestingly, if writing to a register \(R_i\) wouldn't lead to a value being decided, then the client has the freedom to write any value of their preference. This implies that a more relaxed condition could be proposed. However, this relaxed aspect is not significant in the current context, so it is omitted.

- Rule 3: Current decision. A client may only write a (non-nil) value \(v\) to register \(r\) on server \(s\) provided that if \(v\) is decided in register set \(r\) by a quorum \(Q \in \mathcal{Q}_r\) where \(s \in Q\) then no value \(v^\prime\) where \(v \neq v^\prime\) can also be decided in register set \(r\).

- Rule 4: Previous decisions. A client may only write a (non-nil) value \(v\) to register \(r\) provided no value \(v^\prime\) where \(v \neq v^\prime\) can be decided by the quorums in register sets \(0\) to \(r − 1\).

Implementing rule 1 and rule 2 is straightforward. We will not delve into their details in the later sections. Instead, our focus will be on providing guidance on the correct implementation of rule 3 and rule 4.

How the Single-Decree Synod Implements the Correctness Rules

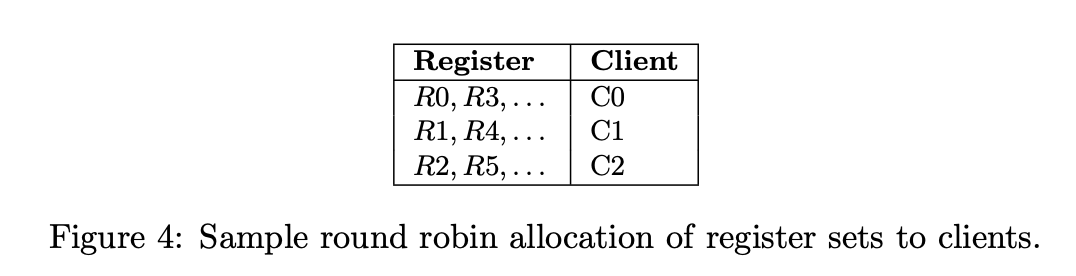

The Single-Decree Synod employs disjoint quorums to implement rule 3, whereby all values written to a particular register set must be identical. This can be achieved by assigning register sets to clients and requiring that clients write only to their own register sets, with at most one value. In practice, this could be implemented by using an allocation such as that in Figure 4 and by requiring clients to keep a persistent record of which register sets they have written too. We refer to these as client restricted configurations.

For those familiar with The Part-Time Parliament, a useful correspondence can be drawn between register sets in the current paper and the concept of ballots in Paxos.

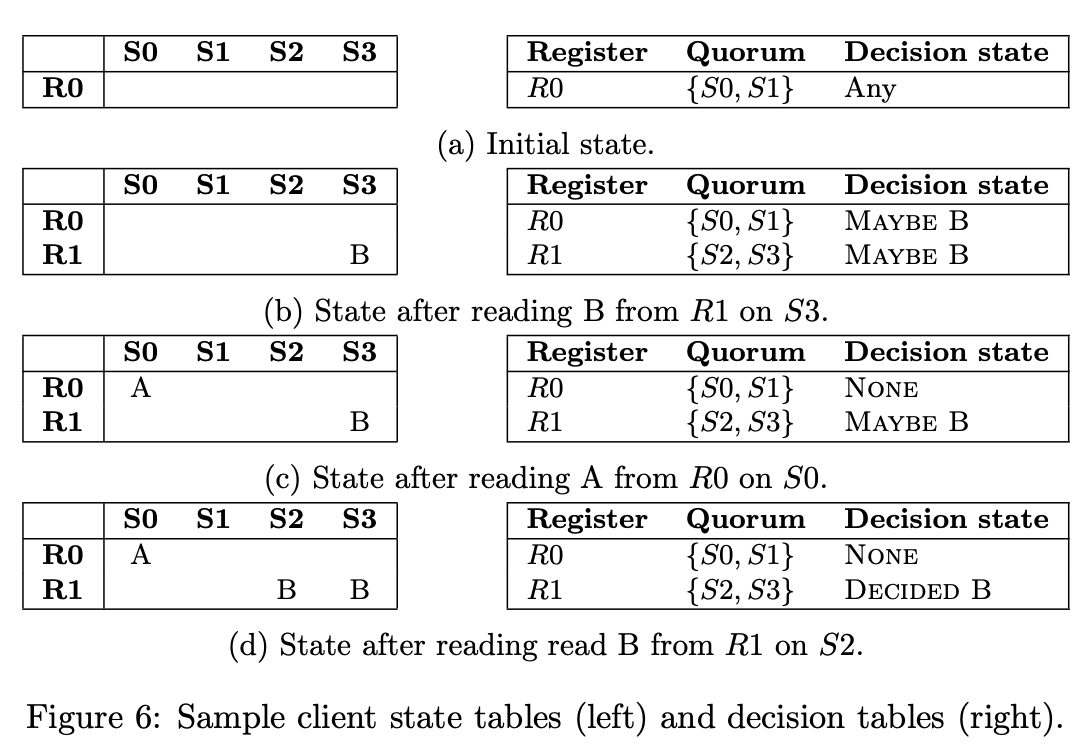

Upholding rule 4 presents a more formidable challenge. A tool we can utilize to address this difficulty is the decision table. Each client's state table consistently contains a subset of the values from the global state table, which is a consequence of the registers being write-once. Consequently, each client possesses the capability to generate a decision table drawing from their individual local state table. At any given time, each quorum is in one of four decision states:

- \(\text{Any}\): Any value could be decided by this quorum.

- \(\text{Maybe}(v)\): If this quorum reaches a decision, then value \(v\) will be decided.

- \(\text{Decided}(v)\): The value \(v\) has been decided by this quorum; a final state.

- \(\text{None}\): This quorum will not decide a value; a final state.

Here are the rules that govern the update of the decision table for client-restricted register sets:

- Initially, the decision state of all quorums is \(\text{Any}\).

- If there is a quorum where all registers contain the same value \(v\) then its decision state is \(\text{Decided}(v)\).

- When a client reads a non-nil value \(v\) at a specific register \(R_r\) (which is one register in the register set \(r\)),

- According to client restricted configurations, only one client can write a singular value, \(v\), to register set \(i\).

- According to Rule 4, prior to the client writing the value \(v\) to register sets \(r\), it must have already ensured that no other value \(v^\prime \neq v\) can be decided by the register sets ranging from \(0\) to \(r - 1\).

- Consequently, we can update the decision state as follows. For all quorums over register sets \(0\) to \(r\),

- The decision state \(\text{Any}\) becomes \(\text{Maybe}(v)\),

- And the decision state \(\text{Maybe}(v^\prime)\) where \(v^\prime \neq v\) becomes \(\text{None}\). The client restricted configurations ensure that only one value can be written to this register set. If the current state is \(\text{Maybe}(v^\prime)\), then the final state can either be \(\text{Decided}(v^\prime)\) or \(\text{None}\). However, when a client writes a value \(v\) to register \(R_r\), it must adhere to Rule 4. This rule stipulates that the client must ensure no other value \(v^\prime \neq v\) can be decided for this register set. This requirement implies that the final state cannot be \(\text{Decided}(v^\prime)\). Therefore, the only possible final state is \(\text{None}\).

There are numerous ways to finalize every decision state of preceding register sets to end states (\(\text{Decided}(v)\) and \(\text{None}\)). A straightforward but inefficient way is to simply wait. However, the Single-Decree Synod employs a faster and simpler method, which I term "fence-and-read-majority". Before writing to any registers in register set \(r\), the client requests all servers to place a "fence" on the registers of register sets from \(0\) to \(r - 1\): if a register state is unwritten, the server writes "nil" to it to prevent further writing; if not, it does nothing. The server then returns the value post-fencing. It's important to note that this fence-and-read-majority is an atomic action on each server. After collecting a majority (not all) of responses from the fence-and-read-majority action, the client can create a decision table that excludes \(\text{Any}\) states, instead only including \(\text{Maybe}(v)\), \(\text{Decided}(v)\), or \(\text{None}\) states. Given that each register is written to only once, the client's local state table will invariably be a subset of the global state table. Consequently, the local decision table will remain consistent with the global decision table both now and in the future. Based on this local decision table, the client can then select a value while complying with Rule 4.

A minor optimization is available in this procedure. Instead of calculating all decision states from \(0\) to \(r - 1\), the client only needs to identify the highest register set \(k\) containing the non-nil value \(v\) and then calculate the decision state of register set \(k\). Here, "highest" means that no other registers of register sets from \(k + 1\) to \(r - 1\) in the response have non-nil values. The client then calculates the decision state of register set \(k\).

- Following Rule 4, before the client (which may not necessarily be the same client that writes the value to register set \(r\)) writes \(v\) to register set \(k\), it must have already ensured that no other value \(v^\prime \neq v\) can be decided in register sets from \(0\) to \(k - 1\). This means it's safe for the client to write \(v\) to register set \(r\) without violating Rule 4 on register sets from \(0\) to \(k - 1\).

- According to client-restricted configurations, it's also safe for the client to write \(v\) to register set \(r\) without violating Rule 4 on register set \(k\).

- Since \(k\) is the highest register set and the majority of registers in register sets from \(k + 1\) to \(r - 1\) have been fenced (written to nil), no value can be decided in these register sets. Therefore, it's safe for the client to write \(v\) to register set \(r\) without violating Rule 4 on register sets from \(k + 1\) to \(r - 1\).

You might question whether the client can use the decision state of any register set instead of the highest register set. However, this is incorrect. Let's consider a scenario where a client writes \(v_n\) to register set \(r\) solely based on its observation that the decision state of register \(n\) (\(n < m < r\)) is \(\text{Maybe}(v_n)\). In this situation, the client could potentially write a value that violates Rule 4. This violation can occur because another client may perceive the decision state of register \(n\) as \(\text{None}\) (due to getting register values from a different quorum, resulting in a different decision state) and write a value \(v_m \neq v_n\) to register set \(m\) (\(n < m < r\)). Consequently, \(v_m\) gets decided in register set \(m\), leading to a conflict.

How Fast Paxos Implements the Correctness Rules

Fast Paxos generalises Paxos by permitting intersecting quorum configurations for some register sets, known as fast sets, whilst still utilising client restricted configurations for remaining sets, known as classic sets.

The process to determine which register sets are designated as fast sets and which are classic sets can be somewhat intricate. If you're interested in a more detailed exploration of this topic, I recommend reading the Fast Paxos paper. However, in this discussion, we'll focus on the simplest scenario. We designate register set \(0\) as the sole fast set, with all remaining register sets classified as classic sets. In this setup, a client does not need to be assigned to register set \(0\) nor do they need to ensure that they write to it with only one value. Clients can write many different non-nil values to various registers of register set \(0\).

This introduces a complexity for clients that are preparing to write to register sets with larger indices, such as register set \(1\). Recall that Heidi Howard stated "each quorum is in one of four decision states". However, each register set has multiple quorums, each of which could be in the state \(\text{Maybe}(v)\) or \(\text{Maybe}(v^\prime)\) (where \(v^\prime \neq v\)), or other similar states. This results in the decision table of the corresponding register set presenting as \(\text{Maybe}(v, v^\prime)\). While the Single-Decree Synod avoids this situation by using client restricted configurations, Fast Paxos may encounter this issue. For instance, when a client writes to register set \(1\), it cannot determine the decision state of register set \(0\) as simply as in the Single-Decree Synod. This is because different registers of register set \(0\) can be written with different values, leading to the client receiving different decision states based on different quorums - it could be \(\text{Maybe}(v)\) based on one quorum, and \(\text{Maybe}(v^\prime)\) where \(v^\prime \neq v\) based on another quorum. This situation leaves the client in a quandary - it cannot write to register set \(1\) until it has ascertained that at most one value could potentially be decided on in register set \(0\).

This issue is addressed through the Quorum Requirement. For any round numbers \(i\) and \(j\), if \(j\) is designated as a fast round number, then any \(i\)-quorum and any two \(j\)-quorums will have a non-empty intersection. Let \(N\) be the number of servers, and let us choose \(F\) and \(E\) such that any set of at least \(N - F\) servers is a classic quorum and any set of at least \(N - E\) servers is a fast quorum. In any given round, any two fast quorums, \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), will intersect at least \(2 * (N - E) - N\) servers, represented by \(R_1 \cap R_2\). If we consider \(Q\) to be any classic quorum, there will be at least \((2 * (N - E) - N) + (N - F) - N\) servers in the intersection \(Q \cap R_1 \cap R_2\). Therefore, if we ensure that \(N > 2E + F\), it guarantees that the intersection \(Q \cap R_1 \cap R_2\) is not empty.

How Flexible Paxos Implements the Correctness Rules

We observe that quorum intersection is required only between the phase one quorum for register set \(r\) and the phase two quorums of register sets \(0\) to \(r − 1\). This is the case because a client can always proceed to phase two after intersecting with all previous phase two quorums since Rule 4 will be satisfied.

Revisiting the Proofs

Revisiting the Proof of the Single-Decree Synod

Based on the sketch provided in the current paper, it's clear that a client (denoted as \(C_n\)) writing a different value (such as \(v^\prime\) where \(v^\prime \neq v\)) to a register set (like \(n\)) violates Rule 4 if a value (like \(v\)) has already been decided on a smaller register set (like \(m\) where \(m < n\)). Without loss of generality, we can assume that register set \(n\) is the register set with the lowest index greater than \(m\) that been written with a different value. Our goal is to prove that obeying Rule 4 and adhering to \(\operatorname{B3}(\mathcal{B})\) as proposed by The Part-Time Parliament are equivalent under client-restricted configurations. We will demonstrate this by contradiction, starting with the assumption that client \(C_n\) complies with \(\operatorname{B3}(\mathcal{B})\). This suggests that there should be another register set, referred to as \(k\), where \(m < k < n\). Additionally, the decision state observed by client \(C_n\) for register set \(k\) must be either \(\text{Maybe}(v^\prime)\) or \(\text{Decided}(v^\prime)\). If this isn't the case, and the observed decision states of all register sets from \(m + 1\) to \(n - 1\) by client \(C_n\) are either \(\text{Any}\), \(\text{None}\), \(\text{Maybe}(v)\), or \(\text{Decided}(v)\), it would imply that \(C_n\) is breaching \(\operatorname{B3}(\mathcal{B})\) when writing \(v^\prime\) to register set \(n\). However, this results in a contradiction as register set \(k\) is the register set with the lowest index greater than \(m\) that been written with a different value. This contradiction solidifies our proof.

Revisiting the Proof of Fast Paxos

Fast Paxos demonstrates the correctness of classical Paxos through a method of classification and induction, a process analogous to the section titled "How the Single-Decree Synod Implements the Correctness Rules" in the current blog.