Paper Interpretation - Fast Paxos

The Classic Paxos Algorithm

I have gained an understanding of the classic Paxos algorithm through The Part-Time Parliament. However, the terminology used in this paper differs from that of the current document. To simplify the transition and ensure clarity, I have created a table that aligns the terminologies from both resources.

| The Part-Time Parliament | Fast Paxos | Explanation of Terminology in Fast Paxos |

|---|---|---|

| ballot | round | Different values are not chosen in different rounds. |

| \(\operatorname{nextBal}(p)\) | \(\operatorname{rnd}(a)\) | The highest-numbered round in which acceptor \(a\) has participated. |

| \({\operatorname{prevVote}(p)}_{bal}\) | \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a)\) | The highest-numbered round in which acceptor \(a\) has cast a vote. |

| \({\operatorname{prevVote}(p)}_{dec}\) | \(\operatorname{vval}(a)\) | The value acceptor \(a\) voted to accept in round \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a)\). |

| \(\operatorname{lastTried}(p)\) | \(\operatorname{crnd}(c)\) | The highest-numbered round that coordinator \(c\) has begun. |

| \(\operatorname{cval}(c)\) | The value that coordinator \(c\) has picked for round \(\operatorname{crnd}(c)\). | |

| Step 1 of the Basic Protocol | phase 1a | |

| \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) | Sends a message to each acceptor \(a\) requesting that \(a\) participate in round i. | |

| Step 2 of the Basic Protocol | phase 1b | |

| \(\operatorname{LastVote}(b, v)\) | phase 1b message | Sends coordinator \(c\) a message containing the round number \(i\) and the current values of \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a)\) and \(\operatorname{vval}(a)\). |

| Step 3 of the Basic Protocol | phase 2a | |

| \(\operatorname{BeginBallot}(b, d)\) | phase 2a message | Sends a message to the acceptors requesting that they vote in round \(i\) to accept \(v\). |

| Step 4 of the Basic Protocol | phase 2b | |

| \(\operatorname{Voted}(b, q)\) | phase 2b message | Sends a message to all learners announcing its round \(i\) vote. |

| CP | For any rounds \(i\) and \(j\) with \(j < i\),if a value \(v\) has been chosen or might yet be chosen in round \(j\), then no acceptor can vote for any value except \(v\) in round \(i\). | |

| Theorem 1 in the "A Formal Statement of Three Conditions" section | CP implies that if \(j < i\), then no value other than \(v\) can ever be chosen in round \(i\) if \(v\) is chosen in round \(j\). |

This paper divides the role of priests, as described in "The Part-Time Parliament," into three distinct roles: coordinators, acceptors, and learners. In this restructured model, a learner is said to learn a value \(v\) if, for some round \(i\), it receives phase 2b messages from a majority of acceptors announcing that they have all voted for \(v\) in round \(i\). The paper also maintains the role of the president, now referred to as the leader, who is essentially a special coordinator.

This paper also introduces the role of proposers. Proposers send their proposals to the coordinators. The coordinator for round \(i\) picks a value that it tries to get chosen in that round.

A single process can play multiple roles. For example, in a client/server system, a client might play the roles of proposer and learner, and a server might play the roles of acceptor and learner.

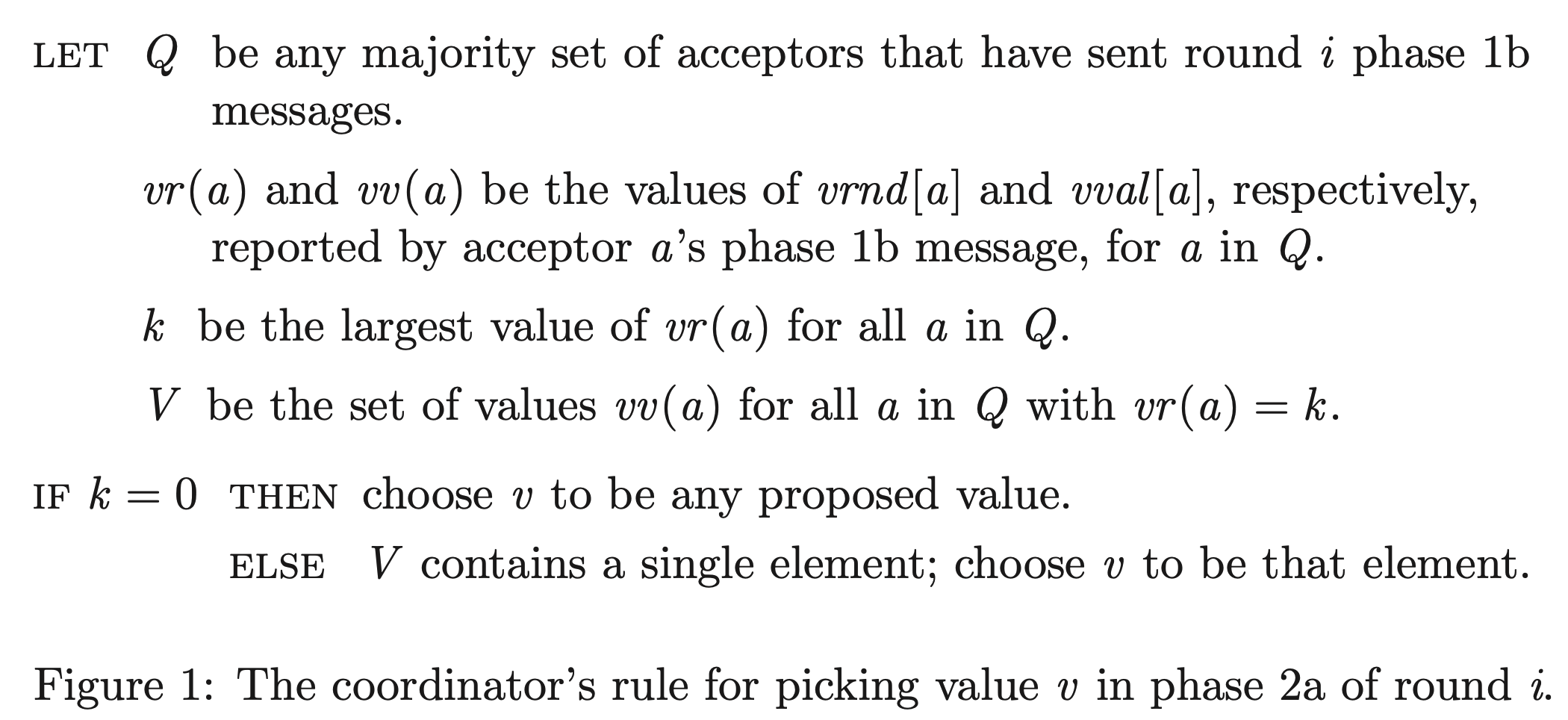

Picking a Value in Phase 2a

"The Part-Time Parliament" establishes the safety of the Synod protocol given conditions \(\operatorname{B1}(\mathcal{B})\), \(\operatorname{B2}(\mathcal{B})\), and \(\operatorname{B3}(\mathcal{B})\). However, this doesn't fully elucidate the safety of Fast Paxos, particularly when dealing with the complexities arising from the protocol's variations. "Fast Paxos" employs a different approach: it starts with the safety requirements and the scenario where phase 2a messages, requesting acceptance of different values, can be sent in different rounds. From this, it deduces the method to select a value in phase 2a. Through this perspective, we can comprehend how to respond to the variations involved in fast rounds. Additionally, I've found that the proof process is much more comprehensible than the one outlined in "The Part-Time Parliament".

We define a value \(v\) as chosen in round \(j\) if a majority of acceptors accept it in round \(j\). Our goal is to validate Theorem 1 from "The Part-Time Parliament," which states that any two chosen values must be the same. Given that any accepted values must have previously been proposed, we can prove Theorem 1 by demonstrating a more stringent property, CP: For any rounds \(i\) and \(j\) with \(j < i\), if a value \(v\) has been chosen or might yet be chosen in round \(j\), then no acceptor can vote for any value except \(v\) in round \(i\).

A useful equivalent to CP that further facilitates the deduction is: For any rounds \(i\) and \(j\) with \(j < i\), if an acceptor has voted for \(v\) in round \(i\), then no value other than \(v\) has been or might yet be chosen in round \(j\).

For a specific round \(i\) and its corresponding value \(v\), \(v\) should fulfill a particular CP property, denoted as \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\): For any round \(j < i\), no value other than \(v\) has been or might yet be chosen in round \(j\).

A useful insight, termed Observation 3, assists in fulfilling \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\): If there is a majority set \(Q\) and a value \(v\) such that every acceptor \(a\) in \(Q\) has \(\operatorname{rnd}(a) > j\) and has either voted for \(v\) in round \(j\) or has not voted in round \(j\), then no value other than \(v\) has been or ever might be chosen in round \(j\). This is quite intuitive. Let's assume there is a different value \(v'\) (\(v' \neq v\)), and some coordinators attempt to have a majority of acceptors accept it in round \(j\). However, each acceptor in \(Q\) won't accept it either because \(\operatorname{rnd}(a) > j\), or because \(a\) has already accepted \(v\) (the enabling condition for the phase 2a action and the unique assignment of rounds to coordinators ensure that phase 2a messages with different values cannot be sent for the same round). Hence, there doesn't exist a majority set \(Q'\) in which every acceptor \(a'\) has accepted or might accept \(v'\) in round \(j\) (It is not possible to find two majority subsets that do not intersect).

Suppose the coordinator has received round \(i\) phase 1b messages from a majority \(Q\) of acceptors. Since an acceptor \(a\) sets \(\operatorname{rnd}(a)\) to \(i\) upon sending \(a\) round \(i\) phase 1b message and it never decreases \(\operatorname{rnd}(a)\), the current value of \(\operatorname{rnd}(a)\) satisfies \(\operatorname{rnd}(a) \ge i\) for all \(a\) in \(Q\). Let \(\operatorname{vr}(a)\) and \(\operatorname{vv}(a)\) be the values of \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a)\) and \(\operatorname{vval}(a)\), respectively, reported by acceptor \(a\)'s round \(i\) phase 1b message, for \(a\) in \(Q\). Let \(k\) be the largest value of \(\operatorname{vr}(a)\) for all acceptors \(a\) in \(Q\). We now consider separately the two possible cases:

- K1. \(k = 0\). \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\) is satisfied regardless of what value \(v\) the coordinator picks.

- K2. \(k > 0\). Because \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a) \le \operatorname{rnd}(a)\) and acceptor \(a\) responds to a round \(i\) message only if \(i > \operatorname{rnd}(a)\), we must have \(k < i\). Then we aim to prove \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\) (for any round \(j < i\), no value other than \(v\) has been or can still be chosen in round \(j\)) by employing a classification approach.

- \(j < k\): We can assume, through induction, that property CP holds. Consequently, no value other than the one proposed in round \(k\) has been or can be chosen in round \(j\). Therefore, if we establish that \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\) holds for round \(k\), it will also hold for round \(j\).

- \(j = k\): By Observation 3.

- \(j > k \land j < i\): Let \(a\) be any acceptor in \(Q\). Because \(\operatorname{vr}(a)\) is the largest round number in which \(a\) had cast a vote when it sent that message and \(\operatorname{vr}(a) \le k \lt j\), acceptor \(a\) had at that time not voted in round \(j\). Thus no value has been or might yet be chosen in round \(j\) (It is not possible to find two majority subsets that do not intersect).

Making Paxos Fast

The normal-case communication pattern in the classic Paxos consensus algorithm is: proposer -> leader -> acceptors -> learners. In Fast Paxos, the proposer sends its proposal directly to the acceptors, bypassing the leader. This can save one message delay (and one message).

In Fast Paxos, round numbers are partitioned into fast and classic round numbers. A round is said to be either fast or classic, depending on its number. Rounds proceed in two phases, just as before, except with two differences:

- The rule by which the coordinator picks a value in phase 2a is modified as explained below.

- In a fast round \(i\), if the coordinator can pick any proposed value in phase 2a, then instead of picking a single value, it may instead send a special phase 2a message called an any message to the acceptors. When an acceptor receives a phase 2a any message, it may treat any proposer's message proposing a value as if it were an ordinary round \(i\) phase 2a message with that value. (However, it may execute its round \(i\) phase 2b action only once, for a single value.)

Maintaining CP after Involving Fast Rounds

In a fast round, proposers send their proposals directly to the acceptors, bypassing the leader. Each acceptor independently decides what proposal message to take as a phase 2a message. Different acceptors can therefore vote to accept different values within the same round.

Consequently, Observation 3 no longer holds true. It's plausible for different phase 2a messages in the same round \(i\) to contain the same \(\operatorname{vr}(a)\), which is \(k\) (where \(k\) is the highest value of \(\operatorname{vr}(a)\) for all acceptors \(a\) in \(Q\)), but have different values for \(\operatorname{vv}(a_1) = v_1\) and \(\operatorname{vv}(a_2) = v_2\). In this scenario, we would still want property \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\) to hold true.

The coordinator's rule for picking a value in phase 2a no longer guarantees consistency, even for a classic round. Consider a situation where a classic round (with a higher id) occurs "after" a fast round (with a lower id). The leader can propose value \(v\) in round \(i\) while maintaining property \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\) if and only if one of the following conditions is met:

- The leader knows that a majority of acceptors voted for value \(v\) in round \(k\).

- Even if all other acceptors with unknown states vote for a value different from \(v\) (for instance, the second majority value \(v'\) voted by \(\operatorname{vr}(a)\) for \(a\) in \(Q\)), value \(v'\) cannot be chosen.

Employing Quorum-Based Approach in Place of Majority Sets

In a system with \(2 * n + 1\) acceptors, suppose \(n\) acceptors reply with the phase 2a message with \(\operatorname{vv}(a) = k\) and \(\operatorname{vr}(a) = v_1\), and \(n\) acceptors reply with the phase 2a message with \(\operatorname{vv}(a) = k\) and \(\operatorname{vr}(a) = v_2\) where \(v_2 \neq v_1\). In this case, round \(i\) must stall and propose nothing. Otherwise, it is highly likely that property \(\operatorname{CP}(v, i)\) would be violated: if the leader proposes \(v_1\) and the unknown acceptor actually accepts \(v_2\), or vice versa.

The example above illustrates that in the worst case, if even a single acceptor out of \(2 * n + 1\) is down, a classic round cannot propose anything. This indicates that Paxos loses fault tolerance under certain circumstances, which is unacceptable. Therefore, it is necessary to generalize the algorithm as follows and continue our discussion based on this generalization: The Paxos algorithm is stated above in terms of majority sets, where a majority set comprises a majority of the acceptors. The only property required of majority sets is that any two majority sets have non-empty intersection. The algorithm trivially generalizes by assuming an arbitrary collection of sets called quorums such that any two quorums have non-empty intersection, and simply replacing "majority set" by "quorum".

Observation 4

With \(Q\), \(vr\), \(vv\), and \(k\) as in Figure 1, a value \(v\) has been or might yet be chosen in round \(k\) iff there exists a \(k\)-quorum \(R\) such that \(\operatorname{vr}(a) = k\) and \(\operatorname{vv}(a) = v\) for all acceptors \(a\) in \(R \cap Q\).

I seem to have a misunderstanding about Observation 4. To clarify, let's consider a specific example. Consider a scenario where there's only one \(k\)-quorum, \(R = \{a_0, a_1, a_2\}\), and \(Q = \{a_0, a_1, a_2\}\) represents any quorum of acceptors that have sent round \(i\) phase 1b messages. If \(a_0\) has voted for \(x\) and \(a_1\) has voted for \(y\) (where \(x \neq y\)) in round \(k\), then not all acceptors \(a\) in \(R \cap Q\) have voted for either \(x\) or \(y\). Given this, and considering that \(R\) is the only \(k\)-quorum in round \(k\), there doesn't appear to be a value \(v\) in \(V\) that satisfies \(\operatorname{O4}(v)\).

Observation 4 asserts that \(v\) has been or might be chosen in round \(k\) only if \(\operatorname{O4}(v)\) is true. There are three cases to consider:

- If no \(v\) in \(V\) satisfying \(\operatorname{O4}(v)\).

- It implies that for every \(k\)-quorum, namely \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\), one of the following cases must hold:

- At least one acceptor in \(Q \cap R_m\) has neither voted nor will vote for any values in the future.

- The acceptors in \(Q \cap R_m\) have already voted for more than one value.

- From this, it's straightforward to infer, \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\) have not chosen or will not choose any value in round \(k\).

- It implies that for every \(k\)-quorum, namely \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\), one of the following cases must hold:

- There is a single \(v\) in \(V\) satisfying \(\operatorname{O4}(v)\).

- This scenario suggests that for every \(k\)-quorum, such as \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\), one of the following cases must hold:

- At least one acceptor in \(Q \cap R_m\) has not voted and will not vote for any value in the future.

- The acceptors in \(Q \cap R_m\) have voted for more than one value.

- All the acceptors in \(Q \cap R_m\) have voted for the value \(v\).

- Then for each \(k\)-quorum, such as \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\), one of the following cases must hold:

- At least one acceptor in \(R_m\) has not voted and will not vote for any value in the future.

- The acceptors in \(R_m\) have voted for more than one value.

- All the acceptors in \(R_m\) have voted for the value \(v\).

- The acceptors in \(R_m\) have voted for more than one value, one of which is \(v\).

- Therefore, it's reasonable to deduce that \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\) have chosen or might choose nothing other than \(v\).

- This scenario suggests that for every \(k\)-quorum, such as \(R_0\), \(R_1\), ..., \(R_n\), one of the following cases must hold:

- There is more than one \(v\) in \(V\) satisfying \(\operatorname{O4}(v)\). In this case we are stuck.

The solution to the dilemma of case 3 is to make that case impossible. We make case 3 impossible by the Quorum Requirement. For any round numbers \(i\) and \(j\):

- Any \(i\)-quorum and any \(j\)-quorum have non-empty intersection.

- If \(j\) is a fast round number, then any \(i\)-quorum and any two \(j\)-quorums have non-empty intersection.

Understanding why the Quorum Requirement prevents case 3 can be somewhat complex. Let's simplify it with an easy-to-grasp example. Consider five acceptors, \(a_1\), ..., \(a_5\). Let's set \(Q = {a_1, a_2, a_3}\), \(R_1 = {a_1, a_2, a_4}\), and \(R_2 = {a_3, a_4, a_5}\). In the fast round 1, acceptors \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) voted for \(x\), while acceptors \(a_3\), \(a_4\), and \(a_5\) voted for \(y\) (where \(x \neq y\)). Following this, in the classic round 2, after receiving phase 1b messages from all acceptors in \(Q\), the coordinator \(c\) identifies two values (\(x\) and \(y\)), both satisfying Observation 4. Here's the twist: If coordinator \(c\) selects \(R_1\) as the 1-quorum, then \(\operatorname{O4}(x)\) is fulfilled (\((R_1 \cap Q = {a_1, a_2}) \land (\operatorname{vv}(a_1) = x) \land (\operatorname{vv}(a_2) = x)\)). Alternatively, if coordinator \(c\) selects \(R_2\) as the 1-quorum, then \(\operatorname{O4}(y)\) is satisfied (\((R_2 \cap Q = {a_3}) \land (\operatorname{vv}(a_3) = y)\)). However, the catch is that \(Q \cap R_1 \cap R_2 = \emptyset\). This condition contradicts the Quorum Requirement, thereby illustrating how the Quorum Requirement can prevent such scenarios.

Let's demonstrate in a more generalized manner how the Quorum Requirement prevents case 3. Assume the existence of a \(k\)-quorum \(R_0\) where all acceptors in \(Q \cap R_0\) have voted for a value \(v_0\). We can prove that \(v_0\) is the only value satisfying Observation 4, and we do this via a proof by contradiction. Suppose there is another distinct value \(v_m\) that satisfies Observation 4 when we choose \(R_m\) as another \(k\)-quorum. By the Quorum Requirement, \(Q \cap R_0 \cap R_m \neq \emptyset\), which means there is at least one acceptor in \(Q \cap R_0 \cap R_m\). Without loss of generality, let's assume this acceptor is \(a_0\). We know that \(a_0\) has already voted for \(v_0\) (since all acceptors in \(Q \cap R_0\) voted for \(v_0\)), and that \(a_0\) is in \(R_m\) (because \(a_0 \in R_0 \cap R_m\)). Consequently, the acceptors in \(Q \cap R_m\) have voted for at least two different values: \(v_0\) and \(v_m\). This is a contradiction.

Choosing Quorums

Let \(N\) be the number of acceptors, and let us choose \(F\) and \(E\) such that any set of at least \(N − F\) acceptors is a classic quorum and any set of at least \(N − E\) acceptors is a fast quorum.

In any given round, any two fast quorums, \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), will intersect at least \(2 * (N - E) - N\) acceptors, represented by \(R_1 \cap R_2\). If we consider \(Q\) to be any classic quorum, there will be at least \((2 * (N - E) - N) + (N - F) - N\) acceptors in the intersection \(Q \cap R_1 \cap R_2\). Therefore, if we ensure that \(N > 2E + F\), it guarantees that the intersection \(Q \cap R_1 \cap R_2\) is not empty.

Given any two classic quorums, they will intersect at a minimum of \(2 * (N - F) - N\) acceptors. Therefore, by ensuring that \(N > 2F\), we can guarantee an intersection between any two classic quorums.

Since the requirements for fast quorums are more stringent than for classic quorums, we can always assume \(E \le F\). For a fixed \(N\), the two natural ways to choose \(E\) and \(F\) are to maximize one or the other. Maximizing \(E\) yields \(E = F = \lceil N / 3\rceil - 1\); maximizing \(F\) yields \(F = \lceil N / 2\rceil - 1\) and \(E = \lfloor N / 4\rfloor\).

Collision Recovery

The round can fail if two or more different proposers send proposals at about the same time, and those proposals are received by the acceptors in different orders. I now consider what the algorithm does to recover from such a collision of competing proposals.

The obvious way to recover from a collision is for \(c\) to begin a new round, sending phase 1a messages to all acceptors, if it learns that round \(i\) may not have chosen a value. Suppose the coordinator \(c\) of round \(i\) is also coordinator of round \(i + 1\), and that round \(i + 1\) is the new one it starts. The phase 1b message that an acceptor a sends in response to \(c\)'s round \(i + 1\) phase 1a message does two things: it reports the current values of \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a)\) and \(\operatorname{vval}(a)\), and it transmits \(a\)'s promise not to cast any further vote in any round numbered less than \(i + 1\). (This promise is implicit in \(a\)'s setting \(\operatorname{rnd}(a)\) to \(i + 1\).)

Suppose a voted in round \(i\). In that case, \(a\)'s phase 1b message reports that \(\operatorname{vrnd}(a) = i\) and that \(\operatorname{vval}(a)\) equals the value \(a\) sent in its round \(i\) phase 2b message. Moreover, that phase 2b message also implies that a can cast no further vote in any round numbered less than \(i + 1\). In other words, \(a\)'s round \(i\) phase 2b message carries exactly the same information as its round i + 1 phase 1b message. If coordinator \(c\) has received the phase 2b message, it has no need of the phase 1b message. This observation leads to the following two methods for recovery from collision.

Coordinated Recovery

Suppose \(i\) is a fast round number and \(c\) is coordinator of rounds \(i\) and \(i + 1\). In coordinated recovery, acceptors send their round \(i\) phase 2b messages to the coordinator \(c\) (as well as to the learners). If \(c\) receives those messages from an \((i + 1)\)-quorum of acceptors and sees that a collision may have occurred, then it treats those round \(i\) phase 2b messages as if they were the corresponding round \(i + 1\) phase 1b messages and executes phase 2a of round \(i + 1\), using the rule of Figure 2 to choose the value \(v\) in its phase 2a messages.

Note that an acceptor can perform its phase 2b action even if it never received a phase 1a message for the round.

Uncoordinated Recovery

Suppose \(i\) and \(i + 1\) are both fast round numbers. In uncoordinated recovery, acceptors send their round \(i\) phase 2b messages to all other acceptors. Each acceptor uses the same procedure as in coordinated recovery to pick a value \(v\) that the coordinator could send in a round \(i + 1\) phase 2a message. It then executes phase 2b for round \(i + 1\) as if it had received such a phase 2a message.

An acceptor picks a value to vote for in round \(i + 1\) based on the round \(i\) phase 2b messages it receives. The nondeterminism in that rule could lead different acceptors to pick different values, which could prevent round \(i + 1\) from choosing a value. This can be prevented by having the round's coordinator indicate in its round \(i\) phase 2a any message what \((i + 1)\)-quorum Q should be used for uncoordinated recovery in case of collision.

When is the Right Time to Start a Fast Round?

If \(E < F\), so fast quorums are larger than classic quorums, the leader will probably choose a fast round number iff it believes that a fast quorum of acceptors is nonfaulty. If \(E = F\), in most applications it will always select a fast round number.