Paper Interpretation - Flexible Paxos: Quorum intersection revisited

Introduction

The steps outlined in the "The Basic Protocol" section of The Part-Time Parliament are as follows:

- Priest \(p\) chooses a new ballot number \(b\) greater than \(\operatorname{lastTried}(p)\),sets \(\operatorname{lastTried}(p)\) to \(b\), and sends a \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) message to some set of priests. Please notice that the quorum \(Q\) has not yet been determined.

- Upon receipt of a \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) message from \(p\) with \(b > \operatorname{nextBal}(q)\), priest \(q\) sets \(\operatorname{nextBal}(q)\) to \(b\) and sends a \(\operatorname{LastVote}(b, v)\) message to \(p\), where \(v\) equals \(\operatorname{prevVote}(q)\). A \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) message is ignored if \(b \le \operatorname{nextBal}(q)\).

- After receiving a \(\operatorname{LastVote}(b, v)\) message from every priest in some majority set \(Q\), where \(b = \operatorname{lastTried}(p)\), priest \(p\) initiates a new ballot with number \(b\), quorum \(Q\), and decree \(d\), where \(d\) is chosen to satisfy \(\operatorname{B3}\). He then sends a \(\operatorname{BeginBallot}(b, d)\) message to every priest in \(Q\). (If \(b \neq \operatorname{lastTried}(p)\), the \(\operatorname{LastVote}(b, v)\) message is a response to a previous \(\operatorname{NextBallot}(b)\) conducted by priest \(p\); so, priest \(p\) just ignores it.)

- Upon receipt of a \(\operatorname{BeginBallot}(b, d)\) message with \(b = \operatorname{nextBal}(q)\), priest \(q\) casts his vote in ballot number \(b\), sets \(\operatorname{prevVote}(q)\) to this vote, and sends a \(\operatorname{Voted}(b, q)\) message to \(p\). (A \(\operatorname{BeginBallot}(b, d)\) message is ignored if \(b \neq \operatorname{nextBal}(q)\).)

- If \(p\) has received a \(\operatorname{Voted}(b, q)\) message from every priest \(q\) in \(Q\) (the quorum for ballot number \(b\)), where \(b = \operatorname{lastTried}(p)\), then he writes \(d\) (the decree of that ballot) in his ledger and sends a \(\operatorname{Success}(d)\) message to every priest.

- Upon receiving a \(\operatorname{Success}(d)\) message, a priest enters decree \(d\) in his ledger.

The steps outlined in the "Paxos" section of Flexible Paxos: Quorum intersection revisited are as follows:

- Phase 1 - Prepare & Promise

- A proposer selects a unique proposal number \(p\) and sends \(\operatorname{prepare}(p)\) to the acceptors.

- Each acceptor receives \(\operatorname{prepare}(p)\). If \(p\) is the highest proposal number promised, then \(p\) is written to persistent storage and the acceptor replies with \(\operatorname{promise}(p', v')\). \((p', v')\) is the last accepted proposal (if present) where \(p'\) is the proposal number and \(v'\) is the corresponding proposed value.

- Once the proposer receives promise from the majority of acceptors, it proceeds to phase two. Otherwise, it may try again with higher proposal number.

- Phase 2 - Propose & Accept

- The proposer must now select a value \(v\). If more than one proposal was returned in phase 1 then it must choose the value associated with the highest proposal number. If no proposals were returned, then the proposer can choose its own value for \(v\). The proposer then sends \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\) to the acceptors.

- Each acceptor receives a \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\). If \(p\) is equal to or greater than the highest promised proposal number, then the promised proposal number and accepted proposal is written to persistent storage and the acceptor replies with \(\operatorname{accept}(p)\).

- Once the proposer receives \(\operatorname{accept}(p)\) from the majority of acceptors, it learns that the value \(v\) is decided. Otherwise, it may try phase 1 again with a higher proposal number.

When comparing the steps outlined in the "The Basic Protocol" section of "The Part-Time Parliament" with those detailed in the "Paxos" section of "Flexible Paxos: Quorum intersection revisited", we observe that Flexible Paxos introduces a significant modification to the classical Paxos.

- Flexible Paxos does not stress that the majority of acceptors who responded with \(\operatorname{accept}(p)\) to the proposer must be the exact same majority of acceptors who sent \(\operatorname{promise}(p', v')\) to the proposer.

- Flexible Paxos permits acceptors to respond to \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\) when \(p\) is greater than the highest promised proposal number.

- Flexible Paxos divides the third step of the Classical Paxos into two distinct components, and integrates them into the first and second phases respectively.

As outlined in "Flexible Paxos: Quorum Intersection Revisited", there are two quorums in the specified version of Classical Paxos, existing respectively in phase one and phase two. This context clarifies Heidi Howard's assertion: "In this paper, we weaken the requirement in the original protocol that all quorums intersect to require only that quorums from different phases intersect. Within each of the phases of Paxos, it is safe to use disjoint quorums and majority quorums are not necessary."

FPaxos

We will differentiate between the quorum used by the first phase of Paxos, which we will refer to as \(Q1\) and the quorum for second phase, referred to as \(Q2\). We observe that it is only necessary for phase 1 quorums (\(Q1\)) and phase 2 quorums (\(Q2\)) to intersect. There is no need to require that \(Q1\)'s intersect with each other nor \(Q2\)'s intersect with each other.

Using this observation, we can make use of many non-intersecting quorum systems. In its most straight-forward application, we can simply decrease the size of \(Q2\) at the cost of increasing the size of \(Q1\) quorums. Notice that the second phase of Paxos (replication) is far more frequent than the first phase (leader election) in Multi-Paxos. Therefore, reducing the size of \(Q2\) decreases latency in the common case by reducing the number of acceptors required to participate in replication, improves system tolerance to slow acceptors and allows us to use disjoint sets of acceptors for higher throughput. The price we pay for this is requiring more acceptors to participate when we need to establish a new leader. Whilst electing a new leader is a rare event in a stable system, if sufficient failures occur that we cannot form a \(Q1\) quorum, then we cannot make progress until some of the acceptors recover.

Implications

Majority quorums

Currently, Paxos requires us to use quorums of size \(n / 2 + 1\) when the number of acceptors \(n\) is even. Using our observation, we can safely reduce the size of \(Q2\) by one from \(n / 2 + 1\) to \(n / 2\) and keep \(Q1\) the same.

Simple quorums

We will use the term simple quorums to refer to a quorum systems where any acceptor is able to participate in a quorum and each acceptor's participation is counted equally. Simple quorums are a straightforward generalization of majority quorums.

Therefore, FPaxos with simple quorums must require that \(|Q1| + |Q2| > N\). We know that in practice the second phase is much more common than the first phase so we allow \(|Q2| < N / 2\) and increase the size of \(Q1\) accordingly. For a given size of \(Q2\) and number of acceptors \(N\), then minimum size of our first phase quorum is \(|Q1| = N - |Q2| + 1\). FPaxos will always be able to handle up to \(|Q2| - 1\) failures. However, if between \(|Q2|\) to \(N - |Q2|\) failures occur, we can continue replication until a new leader is required.

Grid quorums

The key limitation of simple quorums is that reducing the size of the \(Q2\) requires a corresponding increase in the size of \(Q1\) to continue to ensure intersection. Grid quorums are an example of an alternative quorum system. Grid quorums can reduce the size of \(Q1\) by offering a different trade off between quorum sizes, flexibility when choosing quorums and failure tolerance.

Grid quorum schemes arrange the \(N\) nodes into a matrix of \(N1\) columns by \(N2\) rows, where \(N1 × N2 = N\) and quorums are composed of rows and columns. As with many other quorum systems, grid quorums restrict which combinations of acceptors can form valid quorums. This restriction allows us to reduce the size of quorums whilst still ensuring that they intersect.

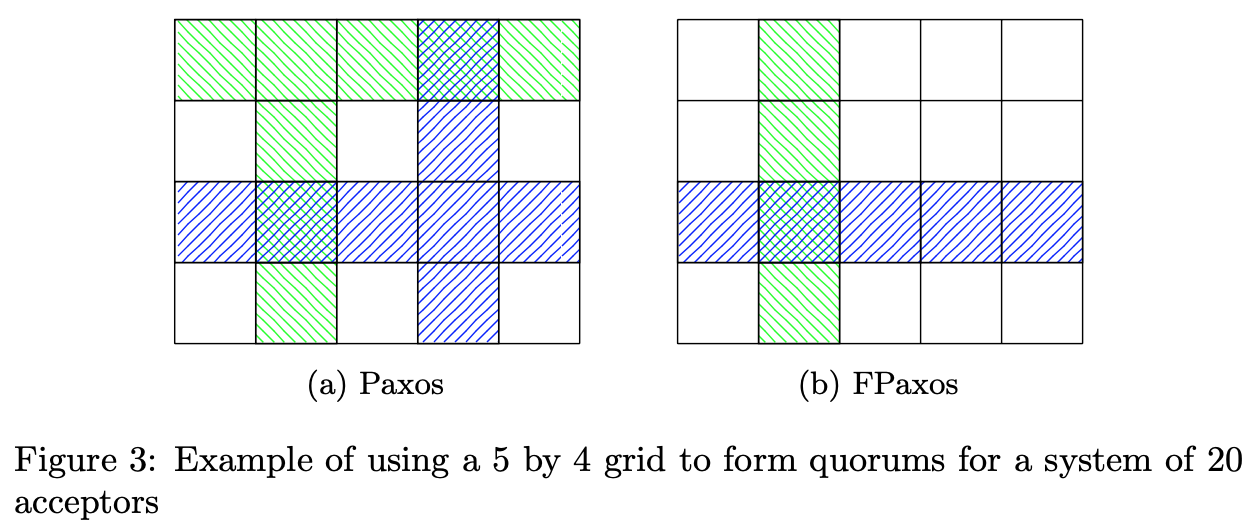

- Paxos requires that all quorums intersect thus one suitable grid scheme would require one row and one column to form a quorum. Figure 3a shows an example \(Q1\) quorum and \(Q2\) quorum using this scheme.

- In FPaxos, we can safely reduce our quorums to one row of size \(N1\) for \(Q1\) and one column of size \(N2\) for \(Q2\), examples are shown in Figure 3b.

Safety

Heidi Howard demonstrates the safety of Flexible Paxos through proof by contradiction and classification discussion. This approach is notably easier to comprehend and retain compared to the proof of the single-decree Synod protocol.

Theorem 2. If value \(v\) is decided with proposal number \(p\) then for any message \(\operatorname{propose}(p', v')\) where \(p' > p\) then \(v = v'\).

Proof is by contradiction, that is, assume \(v \neq v'\). We will consider the smallest proposal number \(p' > p\) for which such a message is sent.

Let \(Q_{p, 2}\) be the phase 2 quorum used by proposal number \(p\) and \(Q_{p', 1}\) be the phase 1 quorum used by proposal number \(p'\). Let \(\bar{A}\) be the set of acceptors which participated both in the phase 2 quorum used by proposal number \(p\) and phase 1 quorum used by proposal number \(p'\), thus \(\bar{A} = Q_{p, 2} \cap Q_{p', 1}\). We can infer that at least one acceptor must participate in both quorums, \(\bar{A} \neq \emptyset\).

Let us consider the ordering of events from the perspective of one acceptor \(acc\) where \(acc \in \bar{A}\). It is either the case that they receive \(\operatorname{prepare}(p')\) first or \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\) first. We will consider each of these cases separately:

- CASE 1: Acceptor \(acc\) receives \(\operatorname{prepare}(p')\) before it receives \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\). When \(acc\) receives \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\), its last promised proposal will be \(p'\) or higher. As \(p' > p\) then it will not accept the proposal from \(p\), however as \(acc \in Q_{p, 2}\) it must accept \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\) (given the value \(v\) is decided). This is a contradiction thus it cannot be the case.

- CASE 2: Acceptor \(acc\) receives \(\operatorname{propose}(p, v)\) before it receives \(\operatorname{prepare}(p')\). When acc receives \(\operatorname{prepare}(p')\), there are two cases. Either:

- CASE 2a: The last promised proposal by acceptor \(acc\) is already higher than \(p'\). Then it will not accept the prepare from \(p'\), however as \(acc \in Q_{p', 1}\) it must accept \(\operatorname{prepare}(p')\). This is a contradiction thus it cannot be the case.

- CASE 2b: The last promised proposal by acceptor \(acc\) is less than \(p'\) then it will reply with \(\operatorname{promise}(q, v)\) where \(p \le q \lt p'\). The value \(v\) will be the same the one \(acc\) accepted with \(p\), under the minimility hypothesis on \(p'\) (\(p'\) is the smallest proposal number for which such a message is sent).

- \(acc \in Q_{p', 1}\) therefore \(\operatorname{promise}(q, v)\) will be at least one of the responses received by the proposer of \(p'\). If this is the only accepted value returned, then its value \(v\) will be chosen.

- Other proposals may also be received for members of \(Q_{p', 1}\). Recall that \(p < p'\). For each other \(\operatorname{proposal}(q', v'')\) received, either:

- CASE (i) \(q' < q\): These proposal will be ignored as the proposer must choose the value associated with the highest proposal.

- CASE (ii) \((q' > q) \land (q' > p')\): This case cannot occur as an acceptor will only reply to \(\operatorname{prepare}(p')\) when last promised is \(< p'\).

- CASE (iii) \((q' > q) \land (q' < p')\): \(p < q < q' < p'\). For an acceptor to have accepted \((q', v'')\) then it must have first been proposed. This is impossible by the minimality assumption on \(p'\) (\(p'\) is the smallest proposal number for which such a message is sent).

Thus the value \(v\) will be chosen, in contradiction to the assumption that \(\operatorname{propose}(p', v')\) was sent.

For a given value \(v\) to be decided, it must first have been be proposed. Thus:

Theorem 1. If value \(v\) is decided with proposal number \(p\) and \(v'\) is decided with proposal number \(p'\) then \(v = v'\).